| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© SEPTEMBER 1966 |

NO STEAM AT

MOUNT EDGECOMBE

FRANK JUX

I liked Mount Edgecombe. You approached it along tree-lined roads, bumping over unprotected road crossings with a glimpse, if you were lucky, of a trail of steam drifting across the canefields to the accompaniment of a clatter of cane trucks and the whistle of a locomotive. But now it has all gone. No more bustle of activity outside a shed built to hold eight steam locomotives. No more grinning Indians riding the footplate up and around the endless curves and gradients, or sitting on the buffer beam feeding sand to the skidding wheels. For Natal Estates Ltd. has followed The Tongaat Sugar Company Ltd. into the abandonment of its 120 miles of "main line" 2 ft. gauge track and will instead fill the country roads with heavily-laden lorries of cane.

An era of rail transport is passing. South African sugar firms are trimming costs in an effort to win more markets, and gradually the once-numerous rail systems are disappearing. integration of the various companies progresses, and Natal Estates Ltd. is controlled by Sir J.L. Hulett & Sons Ltd. in the biggest group in the South African sugar industry. Paradoxically, Hulettís itself controlled by a consortium of other sugar companies, and few firms remain entirely independent.

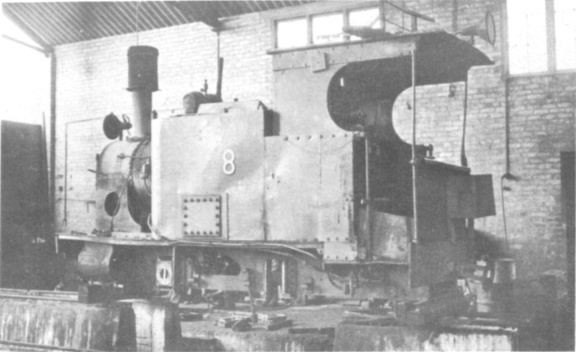

Steam among the cane. Natal Estates Ltd 0−4−0 side tank CORNUBIA,

built by John Fowler, Leeds (F. Jux)

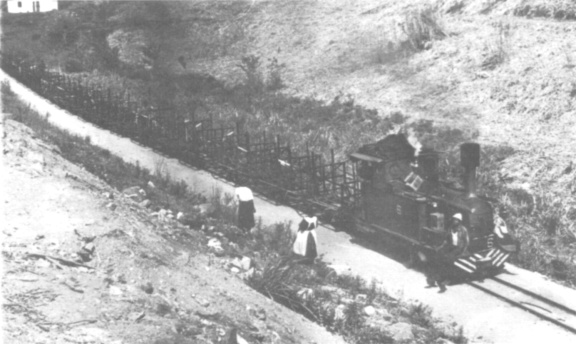

Two locomotives of Reynolds Bros. An Avonside articulated at

Sezela Mill (above) and No.6, an Avonside 0−4−0 side tank at

Esperanza Estate (below) (F. Jux)

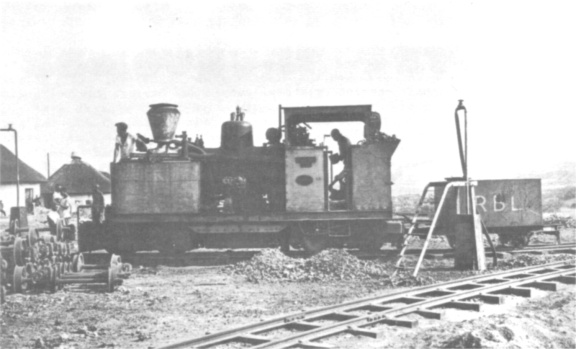

Sir J. L. Hulett & Sons Ltd, Darnall. This 0−4−0 side tank,

built by the Avonside Engine Co. at Bristol, has been fitted

with extended tanks in South Africa (F. Jux)

Sugar was first produced in South Africa in 1851, since when its cultivation has spread to be the main crop of a 250 mile stretch of coastal land in Natal centred on the port of Durban. Over the years millions of pounds have gone into rail equipment, and many more million tons of cane have been moved over the rails. In the 1962/63 cane milling season over ten million tons of cane were handled, a fair proportion of which came from the factoriesí own fields over the cane tramways. Some systems are entirely diesel, but both Tongaat and Natal Estates kept their steam, though the latter had many small diesels for shunting. As elsewhere lack of modernisation has led to replacement.

Mount Edgecombe is twelve miles north of Durban, and almost four miles inland. From the factory its rail system spreads like an octopusís tentacles, but mainly in the coastal direction running around the hills almost to the sea. At least five steam locomotives from their stock of four Fowlers, two Hunslets and two Bagnalls were kept busy on the main lines of the system, while manpower and oxen hauled trucks over temporary tracks in the fields. One or two diesels shunted the not inconsiderable yard at the mill and several others languished outside their own small shed. The engines were an interesting bunch even though the examples of Avonside 0−4−4−0 geared and 0−4−0 side tank sugar designs formerly owned had been scrapped for some time, and Bagnall had not succeeded in selling any articulated type to the company. The speciality, of course, was the Fowler 0−4−2 side tanks, the only examples in South Africa.

With commodious spark arresters and bedecked with baskets of sand they gave a chunky but workmanlike appearance, and did at least their share of the work. The Bagnalls were a dainty 4−4−0T and a big, long 2−6−2T of post-war build. The Hunslets, when I saw them, were both 0−6−2TĎs of typical solid Hunslet design, but one then undergoing repair was in fact reported to have a leading bogie, making it a 2−6−2T when complete.

All in all Mount Edgecombe was one of those places where one promised to return soon with a cine camera. But itís too late now.