| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© FEBRUARY 1974 |

ALDERNEY BREAKWATER

M. SWIFT

The vast increase in maritime trade during the early Victorian period was followed by a demand for harbours of refuge around Britain, and the Government proposed several schemes during 1846‑47. One was for a breakwater some 2,650 feet long from Grosnez Point, on the north side of Alderney in the Channel Islands, enclosing 67 acres of water. This was developed by successive Admiralty Boards during 1854‑58, the final proposal being a west breakwater 6,600 feet long and an east breakwater from Chateau a I'Etoc 1,700 feet long enclosing 150 acres. The cost was estimated at £2½ million pounds.

The contract was let to Thomas Jackson, a contractor who had carried out various railway and canal works during the previous ten years. Alderney was probably his greatest challenge. The island provided only sand and stone - all other material had to be imported, for which the existing harbour was inadequate, and there was no accommodation for workmen. Jackson's first action when preparatory work started on 1st January 1847 was to provide cottages for 1,200 workmen, and construct a railway from the site to Mannez where the Government had purchased a large area to develop as a quarry. About two years later Craby Harbour was built to accommodate tipping barges and the increased traffic of steamboats bringing plant and materials to the island. The breakwater was planned as a rubble bank built up to 12 feet below low water, topped by a masonry wall with the promenade level on the sea side 37 feet above low water, and the quay level on the harbour side 23 feet above low water. The scale of the task was magnified by the depth of the water, which reached a depth of some 150ft.

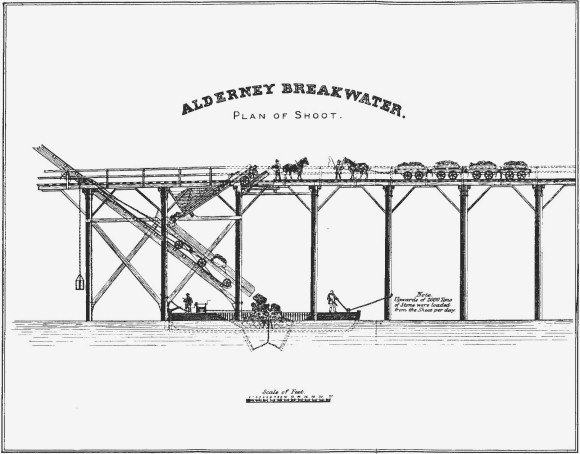

Rubble tipping was started probably in 1849, and by autumn of that year had reached 410 feet from the shore, all tipped from wagons on the end of the bank. Further direct tipping was impracticable and Walker, the Government Engineer, proposed that wagons be loaded on to barges, towed to the site and then tipped. (This method had been used previously at Plymouth.) Jackson proposed an alternative scheme using hopper barges loaded by an adjustable chute to accommodate changes in water level which varied by 17ft between tides. This was adopted, and the 60‑140 ton capacity barges, towed by steam tugs to the site, were able to drop their loads without stopping. By the late 1850's over half a million tons of stone a year were being dumped, at a rate of two to three thousand tons a day.

Although construction of the rubble bank could continue all the year round in calm conditions, the severity of winter storms restricted work on the masonry wall to the period May - September. In April each year staging was erected on the rubble bank to carry track for stone wagons, 20‑ton gantry cranes and "Samson" pile placing machines, which were invented on Alderney. The gantry cranes were loaded on to low "camels" which spanned the track on the promenade and quay levels, and a locomotive then hauled the whole assembly out to the end of the breakwater. In October the procedure was reversed and the equipment stored until the following April.

The foundations of the wall were of concrete and granite blocks, positioned by divers, the remainder of ashlar blocks being set in Medina cement. The promenade and quay levels were pitched with granite setts, inset with rails. The railway on the quay was intended to facilitate landing and embarking troops, that on the promenade having short trailing sidings at intervals and arranged for tipping stone to protect the foot of the wall. Turntables were used on the line, and a short staging built at right angles to the wall. Wagons were run on to the staging where they were normally tipped by hand, but in bad weather a chain attached to a locomotive on the quay level was used.

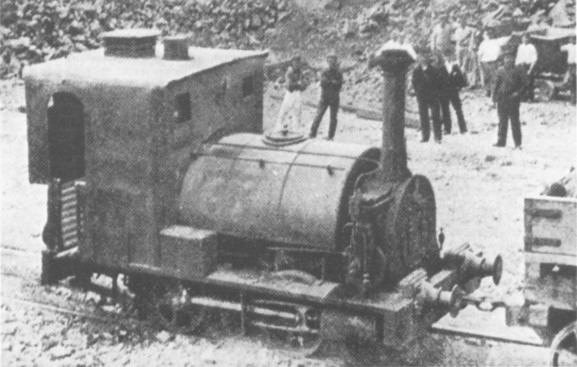

The railway from the breakwater to Mannez quarries was 2½ miles long, laid to standard gauge[*] with 65lb double headed rails. A branch ran about half a mile to Craby Bay where shingle was excavated for making concrete blocks. The first two locomotives were six coupled with four wheel tenders, named VETERAN and FAIRFIELD. These were replaced by two six coupled tank locomotives BEE and SPIDER, and a four coupled tank locomotive WAVERLEY built by Henry Hughes of Loughborough. 300 to 400 four wheel 5‑ton capacity end tipping wagons were used to carry stone over the railway, and a few survived at least into the 1920's.

Mannez quarries had a face 75 feet high, and all the stone used to build the breakwater was obtained from these quarries. The rubble stones weighed 3 to 15 tons each, and the ashlar blocks up to 30 tons. Stone was loaded by over forty 15‑ton cranes, fixed so that two could be used to lift large blocks. The dressed stone was stocked under travelling gantries to facilitate loading at short notice.

* A drawing of the "camel" and gantry shows 7 feet gauge track, but all other plans show standard gauge and this may be an error by a draughtsman familiar with similar works where the Brunel gauge was used.

On 10th August 1854 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert arrived in Alderney to inspect the works. The railway was cleared of obstructions and a locomotive tender converted into a carriage to convey the Royal party to the quarries. 'By 8 a.m. the troops were in position, and the breakwater and foreshore thronged with people in their best attire, while some hundreds of workmen, clad in white smock-frocks provided by the contractors, each bearing a round rod as a symbol of authority, interspersed at intervals amid the throng, added to the attractiveness of the scene. At 9 a.m. the Royal party was rowed to the slipway, and landed under a Royal Salute from the Grosnez Battery. The Queen, Prince Albert, Prince Alfred and Princess Helena then entered the railway car, over which a light roof of striped silk had been spread. The carriage was drawn along the railway to Mannez Quarries by two powerful black horses with outriders - the Queen preferring these to the locomotive. The party made the round trip and inspected the fort at Chateau I'Etoc before embarking.'

By 1856 the breakwater had reached a point 2,700 feet from the shore, and construction of the wall then ceased until 1860, but rubble continued to be placed for the bank. The Admiralty also proposed an extension to avoid narrowing the harbour entrance. In September 1864 the head of the wall was finally completed at a point 4,900 feet from the shore, and at the end of March 1866 the works were transferred from the Admiralty to the Board of Trade. Work to repair storm damage and strengthen the rubble wall continued until July 1872, when the Government decided to vote no more money for maintenance. However, the following year the decision was reversed and maintenance continued.

The Henry Hughes locomotive used by Thomas Jackson on Alderney, presumably photographed in Mannez Quarry in later days when used in connection with the maintenance of the breakwater. Note the small inverted vertical engine mounted on the side of the smokebox - possibly for obtaining the engine's water supply - and the (no doubt very necessary) enclosed cab. The original print shows what appears to be a cast brass rampant horse fixed above the lift‑up smokebox door, similar to those familiar on the road engine products of Aveling & Porter of Rochester - perhaps an example of applied decoration by the driver as there is no suggestion that Aveling's were responsible for the construction of the locomotive. (courtesy Ian Allan Ltd)

Jackson's contract lasted for 25 years, the total cost being £1,274,200. (His partner, Bean, was killed on the Caledonian Canal contract during 1847.) Jackson also constructed the extensive fortifications on Alderney during 1847‑57, and St. Catherine's Breakwater, Jersey, during 1847‑56. His site agents at Alderney were Thomas Dixon until 1857, his son John Jackson until 1866, and William Read until 1872. The plant was advertised for sale in "The Engineer" on 14th June 1872, and included "two tank locos", presumably BEE and SPIDER. WAVERLEY was retained by the Board of Trade for maintenance work, but finally became worn out and was shipped back to England in 1889 to be broken up. By the time work on the west breakwater ceased sailing ships had been largely superseded by steam, reducing the need for harbours of refuge, and in fact the east breakwater of the final plan was never commenced. The harbour and fortifications therefore never fulfilled the role for which they were designed, but the development of quarrying, the railway and shipping facilities provided the basis for a flourishing trade in roadstone and building materials which continued until the outbreak of war in 1939.

I would like to acknowledge the assistance of the London Borough of Greenwich Local History Library, the Institution of Civil Engineers and the Narrow Gauge Railway Society Library in providing source material for this article. Further information may be found in "Industry Illustrated," a memoir of Thomas Jackson of Eltham Park, Kent, published in 1884; "Account of the Construction and Maintenance of the Harbour at Braye Bay, Alderney" by L.F.V. Harcourt, M.A., M.I.C.E. (Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Vol.57, session 1873‑74); and the May 1914 issue of "The Locomotive Magazine".