| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© AUGUST 1973 |

MORE UNDERGROUND STEAM

RODNEY WEAVER

RECORD 34 (page 364) and the subsequent correspondence in RECORD 38 (page 114) featured a number of steam locomotives designed for use below ground. Shortly after this the article on compressed air locomotives in RECORD 41 revealed the extensive use of underground steam traction in the bituminous coal and anthracite mines of the eastern United States. In these mines steam traction was well established a century ago and "The Engineer" of 19th and 26th November 1875 described some of the standard mining locomotive designs of Porter, Bell & Co of Pittsburgh, predecessors of the well-known H.K. Porter Co. Locomotives by this builder were then being used underground in the states of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Illinois.

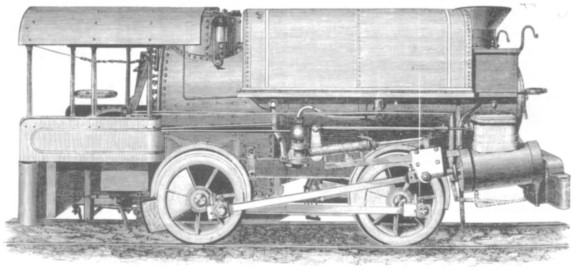

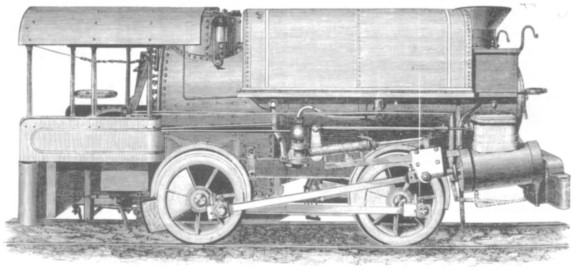

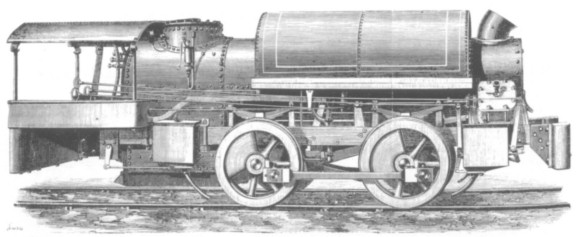

Three designs of Porter locomotive were illustrated, an outside cylinder 0‑4‑0 saddle tank, an inside cylinder 0‑4‑0 saddle tank and an outside cylinder 0‑6‑0 saddle tank.

The first type was apparently designed to achieve minimum overall length, for the driving axle was underneath the firebox and the valve gear (Stephenson's) was driven off the front axle; similar, in fact, to DOLGOCH on the Talyllyn Railway. Indeed the design was very much an Americanised Fletcher Jennings "Patent" locomotive - although as T.R. Crampton had patented the identical layout in 1846 the validity of Fletcher's patent may be questioned. Locomotives of this design were available in three sizes:-

| 7in x 12in cylinders | 2ft 0in driving wheels | Weight 5½ tons * |

| 8in x 14in cylinders | 2ft 2in driving wheels | Weight 7 tons |

| 8in x 16in cylinders |

2ft 4in driving wheels |

Weight 8½ tons |

The outside cylinder 0‑4‑0 saddle tank of the type constructed for the Westmoreland Coal Company.

The second type of 0‑4‑0 was presumably intended to have minimum width: it was therefore longer than the previous design with the driving axle ahead of the firebox. In order to fit the cylinders inside the frames without increasing the height of the boiler centreline the valve chests were angled outwards and the valves driven through rocking levers.

Both types were provided with one crosshead pump and one injector, but only the first type was provided with brakes. The overall height of these locomotives was between 5ft and 6ft depending on the power output. No widths or gauges were quoted, but the outside cylinder version would have been about 2ft wider than the gauge and the inside cylinder one no more than 1ft wider. The saddle tank was constructed to the same profile as the cab, so it is unlikely that the driver could see very much when running forwards. On the other hand there would have been plenty of room in these vast mines to turn locomotives on turntables and it seems probable that they normally ran cab first. Indeed, the inside cylinder locomotive illustrated has its rudimentary chimney angled forwards, suggesting that it was specifically designed to do most of its work in reverse. As the driver had to sit down it would have been more comfortable to work backwards in any case, though whether he would have felt quite so comfortable when at the leading end of a locomotive not fitted with brakes is another matter!

Weighing some 7 tons, this inside cylinder Porter 0‑4‑0 saddle tank had 9in x 12in cylinders and was carried on wheels of 2ft 4in diameter.

Two users of Porter locomotives were mentioned in the article, the Westmoreland Coal Company, who used the outside cylinder machines, and the Consolidation Coal Company, Maryland, who had lines two to three miles long underground and worked over gradients varying from 1 in 28 to 1 in 46. Here a single locomotive had proved capable of replacing twenty to thirty mules yet cost only four times as much as a mule in operating costs. No trouble was experienced with smoke provided ventilation was good, the coal used being fairly clean in any case. Examples of the loads hauled by various sizes of Porter mining locomotive here and at other mines were given as follows:-

|

Size of locomotive |

Gradient |

Load, cars |

Load, tons |

| 7in x 12in | 1 in 28 | 8/10 full | 18/23 |

| 7in x 12in | 1 in 24 | 26 empty | 10½ |

| 8in x 14in | 1 in 20/25 | 10 full | 17½ |

| 9in x 14in | 1 in 46 | 40 empty | 26 |

| 9in x 14in | 1 in 17/21 | 15 full | 22 |

| 9in x 16in | 1 in 37 | 50 full | 75 |

A 9in x 16in locomotive hauling 50 loaded cars up the underground equivalent of the Lickey, its exhaust echoing through the vast subterranean chambers, would surely have been a better subject for the sound recordist than most of the material now on sale!

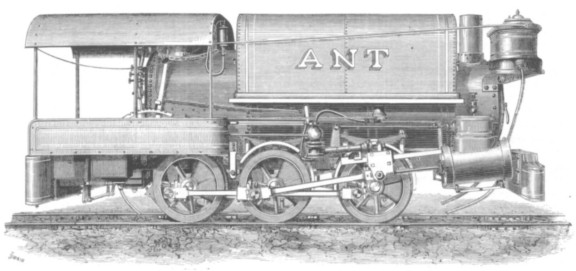

The third Porter design was described in great detail and is of considerable interest as an illustration of contemporary American locomotive practice. This engine, ascribed the name ANT, was a compact 0‑6‑0 saddle tank for 3ft gauge: it had outside cylinders 9in x 14in, 2ft 2in coupled wheels on a 5ft 9in wheelbase and weighed 10 tons in working order. The locomotive, with a maximum height of 5ft 3in and maximum width of 5ft 7in, was fitted with a saddle tank that carried 350 gallons of water (280 Imperial gallons).

ANT was the heaviest of the three underground Porter locomotives described by "The Engineer" : Note the capacious sand box in front of the chimney - in a position more usually associated on an American locomotive with the headlamp bracket!

The striking feature of the design is the extensive use of steel in something far removed from a main-line locomotive. The firebox was of steel, though the rest of the boiler was of wrought iron. Steel fireboxes were standard practice in America by 1875, but despite numerous experiments in Britain nobody produced a really reliable steel box for many years after this. Even Crewe, with unrivalled experience in the manufacture and forming of steel, failed to produce satisfactory steel fireboxes until well into the present century. E.L. Ahrons believed that British designers were too fond of using large, complex plates, quite feasible with copper but less satisfactory in steel with the knowledge then available, whereas American designers used separate plates for each surface of the box. Another interesting feature of the design, in view of the antiquated methods of ash disposal still to be seen on British Railways towards the end of steam traction, was the use of a rocking grate in a small industrial locomotive. The motion was a mixture of ancient and modern: the Stephenson's gear made extensive use of case-hardened steel and renewable bushes yet the pistons retained the old-fashioned spring ring and separate packing twenty years after the introduction of Ramsbottom's piston ring. The driving wheels, which in Porter's small locomotives were distinguished by having seven spokes, had cast iron centres with steel tyres.

Another interesting feature of the specification, which was printed verbatim from Porter's literature, is the precise use of the English language. The locomotive did not have "equipment" or "accessories" - it had "furniture". And it did not have "spanners" - it had monkey, spanner and flat wrenches. Among the furniture were two alternative blast nozzles, provided not to enable the driver to sharpen or muffle the blast but to give different blast cones to suit different chimney heights, the chimney being adjustable to suit available headroom and fitted with an integral petticoat pipe. As in the case of the 0‑4‑0 designs, it seems clear that this locomotive was intended to run in reverse. Once again it is not fitted with any brakes, so perhaps the time-honoured method of stopping a train depicted by early Hollywood film producers was more realistic than it now appears to be! All the same, it seems odd that having adopted steel tyres several years previously Porter were still apparently worried about the effect of braking on the driving wheels. From the figures published in the article it is clear that underground locomotives worked quite heavy trains over steep gradients in a situation where a runaway could have very serious repercussions. Did the drivers have to rely on counter-pressure braking or were men employed to sprag the car wheels at the top of each incline?

Even with good ventilation and large galleries, the employment of any number of these locomotives underground cannot have been very pleasant for the men working close to the main haulage ways and it is no surprise that compressed air and electric mine locomotives so quickly replaced steam traction when they became available some fifteen years later. And having made such efforts to tailor locomotives to the requirements of mines service it is easy to see why Porter enjoyed such a large portion of the compressed air locomotive market.