| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© JUNE 1971 |

Northamptonshire until recently was the home of many industrial steam locomotives which laboured in surroundings far removed from what their nomenclature would imply. But the surviving railways running through green fields and wooded cuttings to ironstone quarries now hear only the moan of the diesel. It is thus ironical that the same county now provides at the British Steel Corporation’s Corby Works the largest remaining fleet of working steam locomotives in heavy industry in this country. However, the impending delivery of five English Electric six‑coupled diesel hydraulic locomotives is expected to bring this state of affairs to a close in the very near future. We regret to say that at the present time permission to visit the railway system at Corby Works has to be withheld. In partial recompense, and as a tribute to some eighty-eight years of steam at Corby. we present this trio of articles. The heading illustration by Trevor Riddle shows No.24 with a load of empty tube wagons, nearing the end of a return trip to BR and about to pass under the Weldon Road before reversing to the Tube Works. Unless otherwise stated the remaining illustrations were photographed in March 1971.

(1) NOW THE SMOKING HAS TO STOP

The shirt and tie engine driver has arrived at Corby Works, where steam locomotive operations will soon be a thing of the past. Works driver Joe Franklin (60), has spent a lifetime on the footplate like his father. He’s not a railway enthusiast but simply looks upon the imminent full "dieselisation" scheme at Corby rather thankfully, in much the same way as an AA patrolman would swap his motorcycle combination for a mini-van. "When you get to my age it’s nice to look forward to a bit more comfort," says Joe, who started as a fireman at the Old Kettering ironworks. He insists that his locomotive, a grimy six−coupled warrior of pre‑war vintage, is not difficult to drive "once you’ve got the hang of things". But Joe’s golden rule is: "Keep a sharp look out and keep the whistle busy!" Joe and his steam loco driver colleagues won’t have much longer to whistle their way around the Corby complex because there will be no steam locomotives left in a few weeks’ time. New diesel units are expected to arrive almost any day now.

Mr. W. McLester, manager of the Iron and Steelworks Traffic Department, looks forward to welcoming the new diesels, "You could hear the old steamers clanking about right across the other side of the works, and it was always said that a steam engine would run even with a wheel missing. The trouble with steam engines is over spare parts and the water at Corby has never been really suitable for the thirsty steam locos because it contains too much lime." Mr. McLester believes that all drivers are equal in diesel units because it’s just a matter of pulling a handle – and away you go. "On the steamers it all depended on the driver. If he ran out of steam then work stopped." With a warm cabin, and smoke, steam and coal a thing of the past, many Corby drivers are already arriving for work wearing a white shirt and smart tie.

(Reproduced from "Steel News", the newspaper of the British Steel Corporation, issue No.42, dated 18th March, 1971, by kind permission of the Editor.)

(2) STEAM FINALE

TREVOR RIDDLE & ROGER WEST

During the early months of 1971, along with some 26 diesels of varying type, power and age, twelve steam locomotives remained at Corby Works. Survivors after the earlier partial dieselisation, and originally part of a larger stock built up by Stewarts and Lloyds from the 1930’s, the engines are, with one exception mentioned later, a group of Hawthorn Leslie 0‑6‑0 saddle tanks, with 16in x 24in outside cylinders. Built to their manufacturer’s then standard specification the first six of these locos were delivered new at the works in 1934, to coincide with the completion of the expansion programme decided on in 1932 - a development which was the first step in taking Corby from a smallish village, with three blast furnaces fed by local ironstone, to the sprawling town and steel works complex it is today. Further locomotives followed in batches and singly until 1941 when HL’s successor, Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns, despatched number 23. A similar locomotive, 40, built much earlier in 1919, had been taken over from the North Lincolnshire Iron Co Ltd in 1931; as it was supplied to NLI when Stewarts & Lloyds controlled that Company (1918-1931) it was probably nominally owned by S&L at the time of acquisition. Experience with this locomotive may have led to the adoption of the updated 16in design as a standard for the Works traffic at Corby, a design which even now is still very well thought of by the drivers. As might be expected of a works with a large number of locomotives and good engineering facilities, the practical experience of operating and maintaining the engines over the years has resulted in a good many detail alterations to the original design; the more obvious external differences can be determined from the accompanying illustrations, though mention may be made here of the cab windows. The enlarged timber framed openings to the front of the cab and the additional side ones were provided some time after World War 2 to provide better all‑round visibility. The rear windows were also enlarged and fined with internal sliding glazed frames. One locomotive, 13, acquired a chime whistle in place of the more standard type.

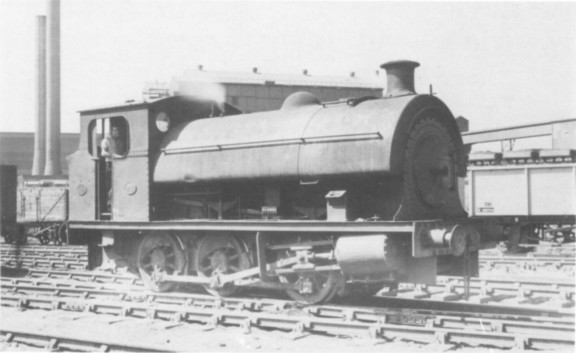

20 in July 1951. Depicts the 16in locomotive in more or less its original form. The chimney and flared coal bunker profile differ from those shown on later photographs, and there are also other differences. (G. Alliez)

By far the most interesting alteration, however, was the fitting of some of the engines with oil-burning equipment. An original experiment some twenty years ago involved converting IRONWORKS No.1, a 1911 Barclay 0−6−0 saddle tank and one of the first Corby Ironworks locomotives to burn tar; this does not seem to have been particularly promising and it reverted to coal-firing. In the late summer of 1960, however, alterations made to Hawthorn Leslie 23 were more successful, and after some nine months’ experience seven of the standard locomotives (12, 14, 15, 16, 18, 23 and 32) were treated similarly over the succeeding two years. The system, devised at Corby Works, consists of a burner mounted in the bottom of the existing ashpan. This is fed with oil, from a tank mounted in the original coal bunker, and with steam, to distribute the oil within the firebox; the steam supply is taken from the dome through a lagged pipe running across the top of the saddle tank and into the cab. A brick arch protects the tube ends from the fierce heat and provides a better circulation of gases in the firebox; the base of the box is also bricked round to a height of twelve inches or so. Two steam supplies, separately controlled, are provided at the burner, one to atomise the oil on entering the fitting, and the other to jet the spray around the firebox. Controlling the amount of steam at these valves gives varying intensities of fire. Steam is also provided to heat the oil tank (it is not always necessary to use this) and to clean out the oil feed pipe and fitting. The oil fuel tank contains 600 gallons and is fitted between and below the rear cab windows, the bunker being extended rearwards slightly to provide the necessary volume. Before the fire can be lit steam pressure has to be available for atomisation of the oil within the firebox. A supply is therefore provided at the loco shed (from a reduced works supply of 50lb) which is connected by flexible pipe into the control fitting, whilst a valve on the supply pipe from the loco boiler is turned off. This stationary source is thus used until a sufficient pressure has been reached (50lb) for the engine’s own boiler to take over. To light the fire, burning cotton waste is thrown into the firebox; it is then possible to ignite the burner by opening the steam valve and jetting valve and then the oil source, after first making sure the firedoors are shut and the blower is on! An air line is provided at the shed in place of the blower until the engine has its own steam. Heated and lagged elevated tanks at the "diesel end’ of the shed form the fuelling point, the oil itself being Victaulic. The conversions are reasonably successful, but the locomotives are somewhat heavy consumers of water and cannot be left for long without losing pressure, due to the transient nature of an oil fire compared with a coal one. When the first changes to oil were made, one locomotive – possibly 18 – was loaned to the Minerals system for trials from Gretton Brook shed. (Has any reader a photograph of the Works loco on a Minerals train?)

A November 1967 shot of number 16 hauling loaded tube wagons to the South exchange sidings. Note the oil fuel tank in the extended bunker space and the steam pipe from the dome. (T. Riddle)

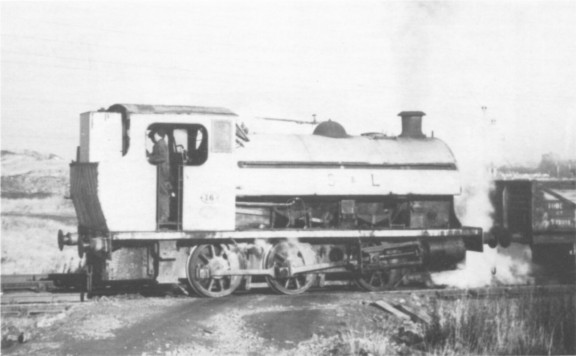

After some years hard work in grimy surroundings. 14 contrasts sharply with her recently repainted sister engine, 21. (R. E. West)

A rear view of 14 at the locomotive shed shows the inevitable result of oil-firing on its appearance. (R. E. West)

This drawing, by Roger West, shows a standard Hawthorn Leslie in its final guise as an oil-burner. It is from measured sketches of 14, which in the early months of 1971 was the Platelayers locomotive.

The locomotives are fitted with Gresham & Craven combination injectors mounted on the boiler backplate and since experience had shown the internal steam delivery pipes to these were subject to corrosion, many engines have had new connections made, some with the steam supply from the existing turret above the boiler backplate, others with the left hand injector served from the steam pipe to the oil-burner controls, Considerable variations exist between different locos in this respect.

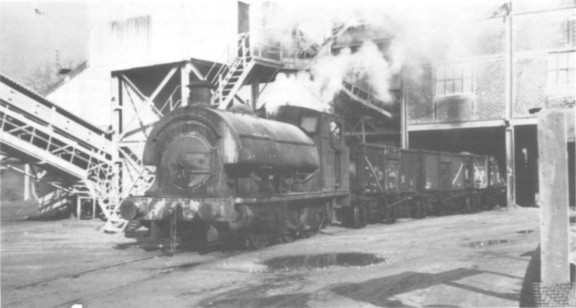

The other surviving loco, "the odd man out", is one of the Hunslet "50550" series with 18in x 24in cylinders (see RECORD 23) originally intended for the ill-fated "Islip Orefield Development Scheme". When sent to Corby Works 24 (Hunslet 2411 of 1941) was used on the Ore Bank, and later worked the hot iron ladles between the blast furnaces and the steel-making plants: but in more recent years it has been regularly used on tube works duties – all jobs on which its additional power was useful. Besides being altered to oil-firing this engine was also modified by placing the previously underhung springs in new positions above the axleboxes. In April1971 24 was out of use owing to damaged motion.

From the 1950’s all locos, steam and diesel, have been painted buttercup yellow, with red wheels and coupling rods and black fittings, and, in the case of steamers, lettered S&L in black on the saddle tank: the 16in locos as a class seem to be known as the "the S&L’s" by the enginemen, other locos not generally having been so adorned. There are variations in the detail of the painting, mostly with regard to the extent, or existence, of black and yellow dazzle striping. This livery was adopted to make them more easily visible in the works, but owing to the dirty conditions which erode the paint, the colour gradually deteriorates to a "steelworks black". In the autumn of 1970, 21 received an overhaul involving the fitting of a new boiler which had been standing spare for a number of years. The axleboxes were renewed, attention given to the motion, etc. and presumably she will be the last loco to have such repairs and renewals. 21 was repainted and lettered BSC, probably the only steam locomotive in British Steel Corporation ownership to achieve this distinction.

In April 1971, at the time of writing, there are two regular steam jobs although, as three further engines are steamed as standby for diesel failures or for occasional or extra duties, three or four engines will usually be at work at any one time. This is out of a total of eight in more or less regular usage, although in March 1971 one of these, 19, was put to one side with slight accident damage. A further four are dumped at the loco shed in various stages of abandonment. The remaining regular jobs are shunting the Electric Furnaces and working the Lime Plant both within the depths of the works area. The former involves transferring scrap – internal scrap in the form of waste from the steel-making activities – to the Electric Furnace for re−making, and the latter duty is the delivery of lime from the plant to the Basic Oxygen Steel Plant. Delivered to the processing plant in main line wagons, the lime is subsequently discharged into large square bins, or boxes, placed on four wheel flat wagons, the bins being lifted off at the lime burning furnace by overhead crane by their two large trunnions. Although nominally a job for a diesel, a steamer until recently often deputised in working the slag ladles from the Blast Furnace front side, down to beneath the Rockingham Road bridge – a good vantage point for enthusiasts – and then setting them back into sidings to be taken over by a diesel for the mile journey to the Blast Furnace slag tips at the Tarmac Plant. The waiting emptied ladles are then returned to the Blast Furnace front.

At the Tarmac Plant the tipped slag is eventually crushed and graded to form road making material. Much is sent away by road as tarmacadam but fine crushed slag is also sent away by rail in 16−ton mineral wagons and this traffic is sufficient to warrant lengthy shunting by a works steamer on two days a week. A further duty is working, as necessary, the Platelayers train – which consists of two or three flat wagons and a 1932 Wolverton-built six-wheel van. This is usually worked by an oil-burner. Until fairly recently a steam loco could occasionally be seen on the dieselised Tube Works shunt. This latter working includes a two mile haul on a double track line through to the British Railways sidings close to Corby station; the run is made partly through open wasteland, a relic of Lloyds Ironstone’s early ore-mining activities in the area. This task was, as mentioned earlier, for many years the preserve of No.24.

Summary of Hawthorn Leslie 16in x 24in locomotives at Corby Works

|

running number |

builder’s numbers |

built | position in March 1971 |

| 11 | 3824 | 1934 | scrapped about June 1969 |

| 12* | 3825 | 1934 | partially dismantled; and parts used to keep other engines in repair |

| 13 | 3826 | 1934 | regularly used |

| 14* | 3827 | 1934 | regularly used - reserved for display by Corby UDC |

| 15* | 3836 | 1934 | regularly used |

| 16* | 3837 | 1934 | out of use - sold for preservation |

| 18* | 3896 | 1936 | regularly used |

| 19 | 3889 | 1936 | out of use (slight collision damage) |

| 20 | 3897 | 1936 | regularly used |

| 21 | 3931 | 1938 | regularly used |

| 22 | 6944† | 1940 | regularly used |

| 23* | 7025† | 1941 | scrapped about June 1969 |

| 32* | 3888 | 1936 | out of use |

| 40 | 3375 | 1919 | scrapped about June 1969 |

* locomotive converted burn oil fuel - others remain coal-fired

† built by Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns Ltd, successors to Hawthorn, Leslie & Co Ltd who built the remaining locomotives listed

Despite the seeming success of the oil fuel conversions it is noticeable that all but one of the scrapped or withdrawn engines are in this category, and it is the coal burners that are in the majority as working units at the end. One is tempted to conclude that the vicious oil fires have not been kind to the boilers. It is generally not considered suitable to send oil-burners on the two regular jobs, due to the ashpan mounted oil-burning equipment being particularly vulnerable to damage from scrap lying between the rails in the Blast Furnace areas; the Tarmac working has similar hazards and in the past oil-burners were not normally sent to the Tube Works.

Two of the remaining locomotives have already been secured for preservation. 16 has been purchased privately, whilst 14, which is still very active, is earmarked for purchase by the Corby Urban District Council for installation as a children’s attraction in West Glebe Park, although consideration also seems to have been given to placing it in the Town Centre as a more historic display in its original livery.

In conclusion we should like to thank local Society members and friends for details of recent observations which have made this article possible.

(3) TUBE WORKS REMINISCENCES 1965-1968

"BEMBRIDGE"

From 1965 to 1968 I worked for Stewarts & Lloyds Ltd at Corby Iron and Steel Works. My new office directly overlooked the Tube Works marshalling sidings, and from other parts of the building it was possible to see a further considerable area of the works. Not surprisingly, I took a keen interest in the railway system. In 1965 one of the three locomotives regularly employed in the Tube Works worked on a day shift basis, The other two were on twenty-four hour duties, and I will deal with these first.

A posed photograph of 21 showing the possibly unique application of the BSC initials to a steam locomotive. (T. Riddle)

One locomotive was continually engaged in collecting loaded wagons from various loading bays in the Tube Works and working them to the marshalling sidings. These were about half-a-mile long and at their widest consisted of about six loops and five dead end roads. The other engine working round the clock would take these loaded tube wagons to the South Sidings, about 2¼ miles away. The sidings were not continually busy; after about 21 hours shunting the engines were idle for a similar period whilst wagons were loaded. Before the start of a shunting session the crews – each engine in the Tube Works carried a crew of three: a driver and two shunters – would spend some time preparing the engines. This often involved shovelling mountains of ash out of the smokebox as well as the more usual jobs of oiling the motion, filling the tank, and making up the fire. Whilst full steam was being raised, engines would have the blowers on, shooting black columns of smoke into the sky. Sometimes it was necessary to return an engine to the shed, either to coal up or to exchange it for another one. One engine would start sorting wagons to be taken to the South Sidings, whilst the other would go around the Tube Works picking up full wagons and returning the empties. Each loading bay had one or more roads served by an overhead travelling crane. The locomotive ran in light pulled out the full wagons, pushed in some empties, and then ran out light again. Most of the tubes were loaded into 22−ton long-wheelbase tube wagons but there was a fair proportion of bogie bolsters. Some of the loading bays were at right angles to the general direction of the sidings and were entered by sharp curves. Most of these were checkrailed but some were laid in grooved tramway type rail.

A view from Rockingham Road as a train of empty slag ladles is brought forward to beneath the overbridge by number 14, before being propelled to the Blast Furnaces in the background. The BR main line northwards to Manton (and previously Nottingham) is at the left and the North exchange sidings in the centre. (T. Riddle)

A full train having been marshalled, the train loco would set it back in the direction of Weldon, under the Tube Works access road and onto a long loop where there was a weighbridge. Wagons were sometimes weighed on this but I imagine that the tubes would be weighed before leaving the works. From here the train moved forwards on to the main line, running on the wrong line for a few yards before crossing over to the correct left hand side. After passing again under the access road and down a steep bank, the descent continued under Weldon Road bridge and towards the Tarmac Plant. Past this plant, near the Stanion Lane bridge, the regulator would be opened for the climb to the South Sidings. This was quite a tough proposition for the Hawthorn Leslies since trains might have as many as thirty wagons and occasionally even more; sometimes enginemen were able to solicit the help of another loco returning downhill light. From our office it was possible to see trains going down as far as the Tarmac Plant; in the cutting beyond we could follow their progress by the sight of their exhausts. About a quarter-of-a-mile after Stanion Lane bridge the Minerals branch to Cowthick and Oakley Ironstone Pits diverged to the left; a little further on was a dump for old wagons, after which the South Sidings could be seen. The gradient steepened in the last few hundred yards and in addition there was a very sharp right hand curve. Locos sometimes stalled on this and the train had to be divided. As the line at the South Sidings ended in a headshunt, full trains had to be set back into the BR exchange sidings proper. Having collected empties and pulled them into the headshunt, the engine ran round and coupled onto the front before setting off for the works; all this was done quite smartly. Depending on the water situation, a stop might be made opposite the Tarmac Plant to fill up on the return journey. Meanwhile the other engine would have marshalled another train ready to take away. The fresh empties would be distributed or left in sidings whilst another load was taken down to the BR sidings. Each round trip took about 45 minutes with two or three trips being made in quick succession.

Another regular job done by one of the Tube Works shunters was the collection, early in the afternoon, of the oil tank wagons that supplied fuel for the Tube Works furnaces. In 1965 these trains consisted of about five S&L internal-user wooden-framed tankers. (By the end of 1967 two long wheelbase SHELL-BP tankers formed the train; by 1968 it was down to a single bogie tanker which rather dwarfed the locomotive.) Often permanent way trains would pass by the offices, or do some work in the vicinity, These were usually powered by one of the two Barclay six-coupled saddle tanks, 6 or 7; when these had gone four-coupled saddle tank WELLINGBORO’ No.3 (Hawthorn Leslie 3813 of 935) was the regular engine, and after that one of the big Hawthorns. For a short time the Minerals Department permanent way train was a regular visitor, powered by 39 RHOS. The gentle comings and goings of this Hudswell Clarke were in direct contrast to those of the vociferous Hawthorns.

There were also the out of course events that occur on any busy railway system. About once a month the breakdown crane was rushed through on some urgent errand. Once a Hawthorn came chuffing through with ten hot slag bogies, and on one occasion a huge gearwheel, weighing about five tons was propelled through on a flat wagon at a speed less than walking pace. I sometimes had to go to the research laboratories which also overlooked the sidings, and one day a permanent way gang was outside removing a couple of sidings with Barclay loco 6 and about seven flat wagons. A ganger called the train forward so that lifted rails could be loaded up and taken away. The driver was a little inattentive; he missed the signal to stop and was alarmed to see the first two wagons run off the end of the rails and bounce over the sleepers. Putting the engine in reverse, he tried to pull them back on again, but this was more than the Barclay could do; so the wagons were uncoupled and dumped to be dealt with by a crane several days later.

Earlier on I mentioned the day shift engine. This had to work a line – we called it the "centre road’ – that ran into the Electrical Resistance Weld (ERW) Plant. Its particular job involved pulling loaded wagons out of the loading bay and taking them up towards the Blast Furnace area; after running forward it deposited them in a siding to await collection by one of the other Tube Works engines. The loco then returned to the ERW Plant with empty wagons. In 1965 the regular engine for this job was WELLINGBORO' No.3 which was painted in the standard yellow "safety" livery and looked very smart when clean. At first its nameplates were painted black but later the letters were picked out in cream paint, The engine made about five trips a day, but most of the time it stood in a siding just outside the ERW Plant, sometimes going to the shed for water; it finally retired there about 4pm each day. The centre road crossed one of the main entrances into the works by a level crossing and on one side of this the track foundations were a little soft, so that locos would bump either up or down something like six inches. The six wheelers didn’t suffer too badly but WELLINGBORO’ No.3 came over the crossing rather like a pram being bumped over a curb, to the amusement of even non-railway minded onlookers.

The normal load of fourteen wagons proved almost too much for WELLINGBORO’ No.3 even on a dry day. If wet, this engine would begin to lose its grip just beyond the level crossing and take fifteen minutes to slip and slither the next hundred yards. During this time the level crossing would be blocked, resulting in disruption of vehicular and pedestrian traffic. A six−coupled Hawthorn eventually took over, but shortly afterwards this regular engine duty was abolished and one of the twenty-four hour engines came over several times a day. This left WELLINGBORO’ No.3 without a job. For a time it was a regular permanent way engine; it was really too small for any other work and was eventually transferred to the company’s Bromford Bridge Tube Works in January 1967.

A train of British Steel Corporation non-pool wagons approaches the Works in charge of 21; a view from the Weldon Road overbridge near the main works entrance. (British Steel Corporation)

13, still a coal burning engine, shunts 16−ton mineral wagons at the Tarmac Plant. (T. Riddle)

Throughout the country coke-cars are nowadays generally handled by electric, diesel or fireless locomotives, and 20 provides an unusual scene at Deene Coke Ovens in deputising for the regular North British diesel which was being serviced at the time. (R. E. West)

In 1965 it was usual for two engines to cover the twenty-four hour duties for several weeks at a time, only going to the shed for washouts or refuelling. Certain engines seemed to be regulars whilst others appeared very infrequently. In 1965 I remember Hawthorns 19 and 20 being used for some time, then Hawthorns 20 and 21 for a lengthy period. Another favourite was Hunslet No.24, which was bigger than the Hawthorns and was no doubt considered more suitable. It used to work for about six weeks, disappear for a little while and then return again. By the end of 1966 this engine was in a poor state, indicated by the numerous clanks, knocks and bangs from the motion. At one time her whistle developed a habit of sticking open which was rather awkward when approaching level crossing gates. No.24 usually managed two of the necessary four toots; then the whistle would stick open until the driver had climbed up the tank and given it the big hammer treatment! Oil-fired engines were not favoured at first although 18 and 16 had fairly long spells on these duties; I understand that the excessive exhaust fumes from the oil-burners precluded their general use on jobs that entailed frequent entering of covered areas such as at the Tube Works. By the end of 1968 locomotives were changed every two or three days and, as far as I know, 23 was the only engine not used on Tube Works duties during the period under discussion. "Rare" engines were 12 and 32, usually to be found around the Blast Furnace area, and 40, which did a few days in March and June1967; its regular job was working the Lime Plant.

By February 1970, the Tube Works duties were completely dieselised. Steam locomotives were things of the past.

"The first locomotive for the American war service in France was erected in twenty working days from receipt of the order at the Eddystone shops of the Baldwin Locomotive Co. The [2−8−0] type is very similar to engines built by the same firm to the order of the British Government. ... These engines have been built by the Baldwin Co. at the rate of about seventy-two per week, the number of employees at its two plants at Philadelphia and Eddystone approximating 20,000 men. It is also stated that the Schenectady Works of the American Locomotive Co. are building three locomotives per day all for Government order."

("The Locomotive Magazine", 15th May 1918. – KPP)

‘During October the Baldwin Locomotive Works broke all records of the establishment in the number of finished engines turned out. The product of the works for that month was 104 engines, and as there were 26 actual working days in the month the output represented an average of four locomotives a day. The best previous record of the works was 96 engines in one month some years ago. This was nearly equalled by the output for November, when 92 locomotives were turned out of the shops. The works are now being run to their utmost capacity, and the firm is making strenuous efforts to turn out 100 engines during December. The Baldwins have just completed and are now shipping ten freight locomotives for the Bone Guelma R., one of the French Government roads in Algiers.’ ("The Railway Engineer" for March 1900, quoting from "The Railway World (Philadelphia)". – KPP)

‘Whereas British locomotive builders seem to more or less delight in hiding their "lights under a bushel," the Baldwin Company seem to delight in publishing particulars of their work broadcast, by publishing at frequent intervals a booklet illustrating and describing in English and French all their most recent productions. Last year the Baldwin Co. completed 908 locomotives, having an average tonnage of 129,000 pounds. For the past ten years the number of engines made has been as follows:—1890, 945; 1891, 899; 1892, 731; 1893, 772; 1894, 313; 1895, 401; 1896, 547; 1897, 501; 1898, 752; 1899, 908. In 1890 thirty-eight more locomotives were completed, but the gross tonnage was much larger. The demand for steel in every branch of industry rendered it impossible to proceed with the desired rapidity, and lessened by fully 100 the number of locomotives manufactured. Many orders were refused, and some had to be cancelled, though 358 engines were exported.’ ("The Railway Engineer," April 1900. There seems to have been an original misprint of the 1890 total. – KPP)