| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© JUNE 1975 |

IRONSTONE NARROW GAUGE

SYDNEY A. LELEUX

The Midlands ironstone field, stretching from Lincolnshire through Leicestershire, Rutland and Northamptonshire to Oxfordshire used to be the home of many narrow gauge railways. The first quarries were almost always linked with the main line by a narrow gauge system, which often had a cable operated incline or an aerial ropeway to overcome the difference in levels - most of the quarries were situated on high ground with the main lines in the valley below. Later quarries had standard gauge systems which obviated the need for transhipment with its associated high costs. Also, the larger equipment was more suitable for mechanical loading as excavators developed in size and popularity. Some narrow gauge systems were converted to standard gauge, but others serving smaller quarries were retained and only closed down when the quarries themselves were exhausted. Twenty years ago an interesting collection of such systems still survived, but all have now gone.

The 3ft gauge Eastwell system, serving a number of quarries in Leicestershire, had at one time been very extensive. The main line tipping dock near Harby station (GN & LNW Joint) was some 250ft below the level of the quarries and a double track cable incline was laid down Harby Hill to overcome this difference, whilst an assortment of locomotives was used between quarry and incline top. The loaded wagons were placed in gently sloping sidings so that they could be run to the incline top by gravity. The wagons were then fastened individually to the overhead cable by a length of chain, one end of which was wrapped several times around the cable and the other hooked to the wagon's coupling. At the fastening point the wagons were held in check by a long horizontal wooden beam which bore against the underneath of the wagon floor. A short distance downhill was a runaway siding.

| Eastwell — incline bottom |

|

At the foot of the incline wagons were unfastened from the cable and run by gravity and their own momentum to one of two tipplers. These had the axis of rotation at rail level and were designed to be stable when containing an empty wagon but top heavy with a full one, so it was only necessary to release the brake for the tippler to make a complete revolution. The empty wagon was then pulled out by hand and run down a short incline to be attached to the cable for the return journey. Reaching the summit, the empties track climbed slightly higher than that for the waiting loaded wagons so that there was a down gradient away from the incline head to carry released empty wagons into the reception sidings. The incline was self-acting with a brakedrum at the summit: at the foot the cable was carried round an idler wheel, which was mounted in a carriage fastened to a tensioning weight. The wagons were of all metal construction with a large wooden buffer at each end.

Similar wagons and tipplers were used at the metre gauge systems serving quarries at nearby Waltham, and at Loddington near Kettering. Both of these systems were closed in 1958 - Waltham in September and Loddington in August. Waltham was closed completely, but Loddington was converted to standard gauge and lasted a few more years. The equipment at Waltham was scrapped in the latter half of 1960, except for one of the trench 0‑6‑0 tanks which went to Towyn Museum and most of Loddington's had gone in 1959, although a few wagons remained for a further three years. The newer locomotive, WILLIAM ELLIS (Avonside 2054 of 1930), lasted until the mid‑1960's when the standard gauge system closed, apparently because the men liked it and would not permit it to be cut up! It is perhaps a pity that it was not transferred to Wellingborough where the gauge was almost the same.

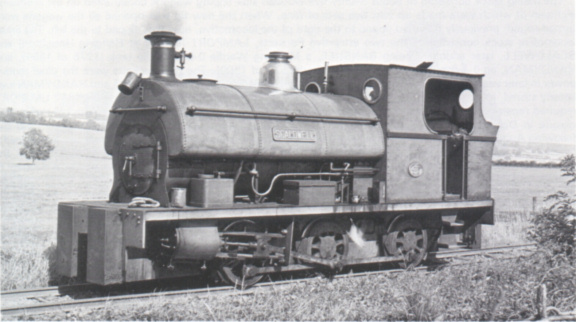

Eastwell

LORD GRANBY, a hefty looking Hudswell Clarke (633 of 1902), poses for the camera in 1954. (G. Alliez, courtesy B.D. Stoyel)

Eastwell MOUNTAINEER (Bagnall 2203 of 1923) takes water at White Lodge on 1st January 1959. Situated on the otherwise abandoned line to older pits at Branston, this water source was used to conserve supplies at the shed for washing out purposes. (R.E. West)

Eastwell closed for regular traffic on 21st October 1959, but the system was kept intact in case the replacement AEC six‑wheel dumpers had difficulty on the hill in winter: they managed, however, and the railway became superfluous. It was last used on 16th August 1960 when the full tubs in the top yard and those on the incline were worked down to the tippler, although (as mentioned on page 14 of RECORD 1) a farewell trip was run for members of the Birmingham Locomotive Club on 28th August. Two of the locomotives, LORD GRANBY (Hudswell Clarke 633 of 1902) and NANCY (Avonside 1547 of 1908), were preserved together with one of the unusual wagons, and the rest went for scrap over the next two years.

The last three narrow gauge steam-operated quarry lines to survive were all situated quite close to one another in Northamptonshire. The first to go, in October 1962, was the Kettering Furnaces system. The ironworks at Kettering dated from 1878 and were supplied with local ore brought in by a 3ft gauge tramway. As the quarries became exhausted and the length of haulage increased, so the original Black Hawthorn 0‑4‑0 saddle tanks were relegated to shunting and replaced on the main line by three Manning Wardle 0‑6‑0 saddle tanks. Rolling stock comprised 2‑ton wooden side-tipping wagons, totalling about three hundred in March 1959, although the highest number noted on a wagon was 360. Kettering was the type of system often replaced elsewhere by standard gauge, but it lasted here as the ore was tipped directly at the ironworks. The ore was still loaded by hand in early 1960, although an excavator had arrived by the following year.

At the works the ore was calcined - mixed with coal and burnt - before being used to charge the furnaces. The calcining was done in bays in a long gantry which comprised a dozen or so parallel brick walls spanned by girders carrying three parallel tipping tracks. At any one time some bays would be alight, some being filled and some emptied. Calcining ceased in April 1959 when the furnaces closed, and about half of the gantry was pulled down and a row of holes knocked in the walls of the remaining section so that a standard gauge track could be laid. Henceforth the ore was loaded into BR wagons and sent to other ironworks.

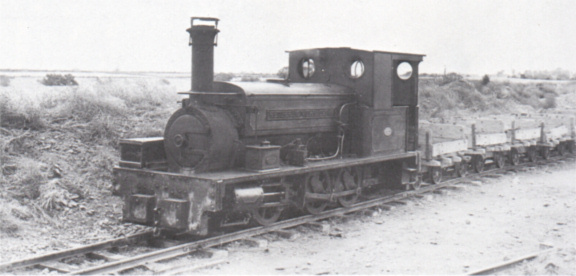

Waltham A far cry from her original haunts, the exiled NANTES (Corpet & Louvet 936 of 1903) plods through grassed over earlier workings to cross the Knipton road before describing a semicircle to the tipping dock. Photographed in 1950. (F. Jones)

Kettering The first wagonload of ore from afresh set about to descend into BR tipplers below. This adaptation of the old calcining bays is described in the article - the right hand track being the only one capable of use from that time. The locomotive is KETTERING FURNACES No.2 (Black Hawthorn 501 of 1879). (R.E. West)

Kettering KETTERING FURNACES No.6 (Manning Wardle 1123 of 1889) stands with a set of wagons. The engine sports a Robert Stephenson & Hawthorns livery, acquired when she visited Forth Banks Works, Newcastle, for overhaul in 1949. Photograph taken in 1955. (G. Alliez, courtesy B.D. Stoyel)

Kettering — furnaces

Kettering — quarries

On a normal day three narrow gauge saddle tank locomotives (two 0‑6‑0 and one 0‑4‑0) would be in steam, stabled in the small corrugated top shed. The others, one of each type, were kept in the large building which had one road for spare standard gauge locomotives (which worked for a week continuously), and one for the 3ft gauge locomotives. The narrow gauge 0‑6‑0 saddle tanks hauled trains to and from the quarries and the 0‑4‑0 saddle tank shunted at the works. Occasionally the latter worked to the quarries when there was an extra load of ore to bring down, but it could manage only twelve wagons, against the usual thirty-six. Six trips were made daily, three by each engine: four in the morning and two in the afternoon. The first locomotive hauled its train to the quarry loop and left it there with sprags in the wagon wheels while it collected half the full wagons from the quarry. It then waited in the other quarry loop for the second train, although if this had already arrived, the first locomotive had a clear run back to the works. The second locomotive then collected the remaining full wagons, put them in the loop, and distributed both trains of empties before returning.

When hand loading was practised gangs of men worked the whole length of the face - say 500 yards - and each gang had two or three wagons to fill, so empties had to be distributed along the length of the quarry. The arrival of the excavator simplified these arrangements: empties were left near it and single wagons were pushed nearer by hand for filling, after which they were pushed farther on ready for collection. In the absence of a locomotive, the rake of empties was periodically moved forward by the excavator. A length of wire rope was attached to the bucket and the leading wagon, then the excavator slewed and racked out its bucket arm, so hauling the wagons along. Loaded wagons were often given an initial push by putting the bucket against the wagon end and slewing, a practice which no doubt accounted for many of the broken wagon bodies in later days.

The main line, two and a half miles long, was laid directly on to the surface of the ground, and the section entering the works was on a gentle grade. Here the 0‑6‑0 saddle tank slowed or waited with its train uncoupled. Meanwhile the works shunter had entered a short siding on the edge of the works. The loaded train drifted down past this siding and then its locomotive accelerated rapidly away to run on to the furthest tipping dock road. As soon as the last wagon had cleared the short siding points, the works shunter rushed out, chased the train and pushed it to the nearer tipping dock. Such a burst of activity simply to save running round was remarkable. The first train was then usually shunted on to the middle road, ready for the second train, and the wagons tipped. Normally the large locomotives were not allowed on the gantry, but occasionally one had to act as yard shunter when both the small locomotives were under repair.

The layout at the works was basically a long curved loop round the water tank, terminating in the tipping dock: the small locomotive shed led off the loop. A long siding ran down to the standard gauge for coaling, and another led to the standard gauge shed. About three hundred yards from the works there was a triangle and several sidings which had served as a wartime ore stockpile. The triangle was used to turn the single side tipping wagons so as to be able to tip the other way.

In addition to the locomotives already mentioned, the line possessed a unique articulated Sentinel geared steam locomotive: this was basically two standard four-wheel units permanently coupled cab to cab with linkages connecting the regulators and reversing gear. Built in 1926 (works number 6412), it did a lot of work when new, but fell out of use when traffic slackened and was scrapped in 1960. After the closure in October 1962 one of the 0‑6‑0 saddle tanks, No.7 (Manning Wardle 1370 of 1897), was used on the thrice weekly track lifting train for a few months. No.2 (Black Hawthorn 501 of 1879) subsequently went to Penrhyn Castle Museum in North Wales, while No.8 (Manning Wardle 1675 of 1906) is preserved locally; the remaining locomotives went for scrap. After the track had been lifted, the bridges were filled in and a year after closure it was hard to believe that trains of ore had ever passed through the fields.

The Scaldwell narrow gauge system was a traditional layout opened in 1913, with a short 3ft gauge line feeding a ropeway which carried the ore down to the Northampton-Market Harborough line (LNWR). A second 3ft gauge line from Hanging Houghton quarries used to connect with this ropeway about halfway along, alternate buckets only being filled at Scaldwell. In 1942, however, a steeply graded and winding standard gauge line was laid to these quarries, after which Scaldwell made sole use of the ropeway. The locomotive, LAM PORT (Peckett 1315 of 1913), was then transferred to join its sister, SCALDWELL (Peckett 1316 of 1913); both were six‑coupled saddle tanks of typical Peckett outline. About thirty wagons remained derelict on the embankment to the tipping dock until the site was levelled in mid‑1963. Most of the wagons were wooden 5‑ton side tippers, as at Scaldwell, but there were one or two smaller wooden end tippers and an unusual home made bogie wagon built in the 1930's for carrying excavator parts and rails. The flat steel girder framework of the body rested on a pair of outside-framed wooden bogies.

Operation of the ropeway ceased in September 1954 and a branch was laid from the standard gauge Hanging Houghton quarries line to a tipping dock near the former Scaldwell ropeway terminal, so that operation of the 3ft gauge line continued much as before.

The quarries were above Pitsford reservoir, and latterly were about one and a half miles from the tipping dock. There was a loop near Holcot road bridge, beyond which the single track line continued towards the western edge of Scaldwell village. A loop also served the 1954 standard gauge tip, whilst yet another served the ropeway tip at the terminus. Just beyond there was a three-in-one point; one track led to the green painted corrugated iron shed with its water tank and coal stage outside, one was for spare wagons, and the third was formerly used as a shunting neck.

Prior to 1954 trains were pulled in both directions, the locomotive running round at Holcot road bridge to push the train to the quarry. At the depot the train ran beyond the tip and then reversed on to the gantry, as this was not strong enough to carry the locomotives. After 1954 empties were pushed all the way to the quarry. The new loop was on a gradient and as the train of nine loaded wagons ran to the upper (depot) end, the rake of empties was allowed to run out of the lower (quarry) end by gravity. The full wagons were then pushed into the top end of the loop and divided into rakes of three for unloading. Meanwhile, the locomotive had returned light down the through road and collected the empties where they had come to rest in a dip a hundred yards away. Three 3ft gauge wagons filled one standard gauge side-tipping dump car (the ore was calcined in a huge embankment alongside BR metals). One of the three standard gauge 0‑6‑0 saddle tanks pushed up six dump cars, left three in a loop by the tip, and waited with the rest while they were filled. It then returned, taking with it the three wagons left on the previous trip, which in the meantime had been run down to the tip by gravity. The empty narrow gauge tippers were collected in the bottom of the loop where the doors were closed. At the instant of tipping they were prevented from overturning by means of clamps through the wheels. The clamps were steel bars of inverted L‑shape, pivoted about a foot below rail level outside the track.

Scaldwell

Scaldwell An immaculately polished SCALDWELL (Peckett 1315 of 1913) basking in the sunshine. (F. Jones)

Scaldwell A workman levers off the catch which retains the wagon body in the horizontal position prior to discharging the contents into the standard gauge wagon waiting below. Note the restraining clamps on the wheels, as mentioned in the text. 7th September 1961. (S.A. Leleux)

The rolling stock consisted of about twenty-five wooden side-tipping wagons constructed on the premises, eighteen of which were made up into two sets of nine. When the new tip was opened all the wagons were turned round; previously they had tipped to the right of the locomotive, now they tipped to the left. The initial locomotive stock consisted of the two attractive Pecketts, LAMPORT (initially at Hanging Houghton) and SCALDWELL, later additions being BANSHEE, a Manning Wardle 0‑6‑0 saddle tank (1276 of 1894), and HANDYMAN, an 0‑4‑0 saddle tank (Hudswell Clarke 573 of 1900). The two Pecketts were the chief motive power in later years, one or other being in steam daily. BANSHEE was scrapped in 1945 and HANDYMAN was latterly stored, at first in the open, then in a small shed by the ropeway tip. In 1961 or early 1962 LAMPORT required repairs which were started but not finished, and SCALDWELL thenceforward handled all traffic until closure in December 1962; it also worked an enthusiasts' trip for the Birmingham Locomotive Club the following August. There had been talk of extending the standard gauge to the Scaldwell quarries, but instead a recession in the industry caused complete closure of the system. SCALDWELL is now preserved at the Brockham Museum in Surrey, whilst HANDYMAN, after a period in store at Cyfronydd on the Welshpool & Llanfair and at the Kinnerley Depot of the Welsh Highland, is presently stored in Derby at the Normanton Barracks depot of the Midland Railway Co Ltd. In addition, wagons were sent to Brockham and to Kettering (to stand with KETTERING FURNACES No.8). The standard gauge locomotives remained for some time after this, being used occasionally to move out calcined ore, but now they too have gone.

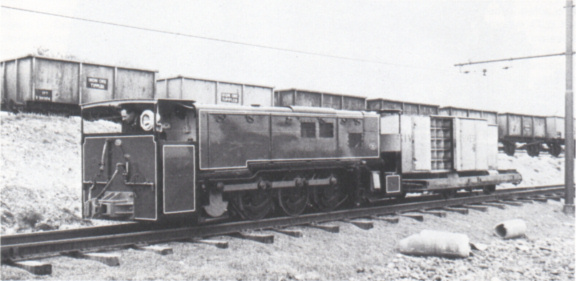

The last of the quarry systems to remain in operation was the 3ft 3in gauge line to Wellingborough quarries, operated by Stewarts & Lloyds Minerals Ltd. The railway had been extensively modernised in the mid‑1930's with two (and in 1942 a third) large Peckett 0‑6‑0 saddle tanks and a fleet of high capacity steel ore wagons. Each wagon, built by G. R. Turner Ltd of Langley Mill, Notts, had a flat steel underframe carrying two open box-like containers. These containers, of about five tons capacity, were removed by a crane using special slings and emptied by inversion in the slings. The provision of wagon springs, brakes and centre buffer couplers was also unusual for ironstone practice. The use of this modern equipment was probably the reason why the railway lasted until 14th October 1966, when the quarries were closed due partly to flooding from former mine workings in the area.

Originally the railway was used to supply ore to the Wellingborough Ironworks but when the furnaces closed in October 1962 the ore was sent to other works for smelting. The quarries were on top of Finedon Hill and situated nearby were several sidings and a weighbridge. Wagons were taken down into the quarries two or three at a time by one of the earlier Pecketts, which worked there all day except for lunchtime, when it returned to the shed. From the quarries the track led straight downhill, with level crossings over two roads, and consequently wagon brakes were pinned down for the descent. Across the river was the single road brick engine shed and several loops. In ironworks days the works shunter left empties here and took the full wagons on, but subsequently the main line locomotives worked through. Beyond the loops was a tunnel, fifty-five yards long, passing beneath the Midland main line, followed by a sharp, checkrailed curve laid in chaired bullhead rail. (The rest of the line was flat-bottom rail on wooden, or in some sections, concrete sleepers.) The line then divided, the branch going to the former calcine bank, while the main line terminated in a number of loops by a mobile crane which was used to unload the ore tubs into standard gauge wagons. Previously the ore had been unloaded into a crusher, and then emptied by conveyor belt into more narrow gauge wagons; each tub was then loaded with 2 or 3cwt of slack coal. So loaded, the wagons were pushed to the calcine bank, which was spanned by an overhead crane fitted with tub slings.

Wellingborough — former Ironworks

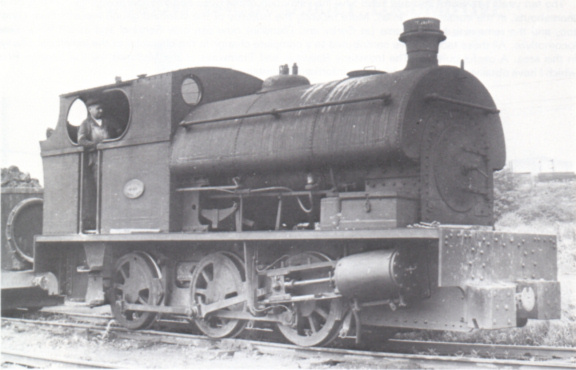

Wellingborough Peckett 1871 of 1934, complete with spark arrester, in 1954. The massive proportions of this 3ft 3in gauge locomotive are such that one could be forgiven for thinking it ran on the standard gauge. (G. Alliez, courtesy B.D. Stoyel)

There were about ninety wagons, plus one converted to carry permanent way materials, and another (with low outward sloping sides) for locomotive ash which was used as ballast. After the closure some tub bodies went to the nearby Cranford quarries for use on the calcining clamp, and the rest were scrapped. The three locomotives survived: No.85 (Peckett 1870 of 1934) went first to the Bressingham Steam Museum before moving on to the Yorkshire Dales Railway at Embsay, whilst No.86 (Peckett 1871 of 1934) and No.87 (Peckett 2029 of 1942) are presently located in contractors' yards at Kettering and Finedon respectively.

One relic of former days was WELLINGBORO' IRON CO. LD. No.4, a Hunslet 0‑4‑0 saddle tank (473 of 1888), which was used as a shunter before being withdrawn and dumped for some years by the locomotive shed, where it was scrapped in 1959. This locomotive, like the ironworks ones, had a green livery with red nameplates. The Pecketts had been black, but in 1964 were repainted green with white running numbers - before this the only means of identification had been their maker's plates.

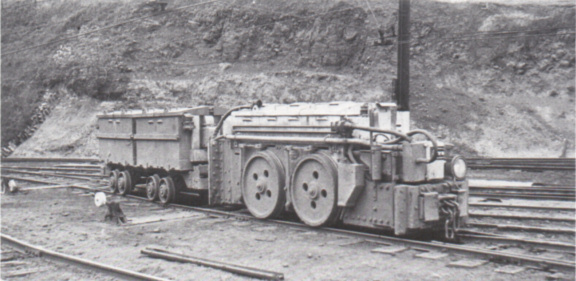

Most ironstone was obtained in the field by opencast quarrying, but some mines were operated. Stewarts & Lloyds Minerals Ltd had a modern, but short lived, mine at Thistleton, near South Witham, Lincolnshire. Opened in 1957 with a 3ft 6in gauge overhead wire electric railway on the main roads and diesel locomotives on the side headings, it had closed by 1966 and the equipment was subsequently sold. A much more extensive mine was at Irthlingborough. Opened in 1918, it had a 3ft gauge system with overhead wire electrics for main haulage and battery locomotives in the workings. Diesels were introduced in quantity in 1963, a new locomotive shed was constructed, and the overhead wire locomotives rebuilt to battery-electric, with most of the batteries carried on separate bogie 'tenders'. All this did not prevent closure, which came in mid‑1965, primarily due to cheaper foreign ore imports.

The ten years between 1956 and 1966 saw the extinction of the once common narrow gauge, usually 3ft or thereabouts, in the ironstone quarries. More recently the majority of the standard gauge systems have closed too, and the remaining two systems (at Corby and Glendon) now use only Sentinel and ex‑BR 95xx diesel locomotives. All these factors have contributed to a complete change in the character of the ironstone railways in this area. A useful guide is 'The Ironstone Railways and Tramways of the Midlands' by E.S. Tonks, from which I have obtained some of the historical information contained in this article.

Thistleton

One of the 0‑6‑0 diesels - Hudswell Clarke DM1216 of 1960 - seen here shortly after delivery. 5th April 1960. (S.A. Leleux)

Irthlingborough A four wheel battery electric (Greenwood & Batley 1567 of 1938) complete with battery 'tender'. 21st May 1964. (S.A. Leleux)