| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© JUNE 1974 |

LIDGETT COLLIERY

TREVOR J. LODGE

Situated some five miles almost due south of Barnsley, Lidgett Colliery was far from the largest of the many pits which have been worked in the locality. Nevertheless, it is of more than passing interest to both mining and railway historian; particularly the latter, as the method adopted for transporting coal a mere two miles or so to Elsecar involved no less than three distinct forms of railway haulage. The colliery was located on the eastern edge of Tankersley Park, an area exploited in the early and middle nineteenth century for its deposits of clayband iron ore. The three shafts utilised by the colliery were, in fact, formerly used in ironstone mining, being sunk in 1830 to the Tankersley Ironstone seam by Earl Fitzwilliam. With three other shafts they supplied local ironworks until about 1877, the Skiers Spring ironstone district being officially abandoned in November 1879. Subsequently two of the shafts, No.3 and No.4, were partially filled in until they only went down as far as the Lidgett coal seam, which was some 200 feet above the old ironstone deposits: they were then both used as downcast and winding shafts. The upcast shaft (No.2) was not filled in, being used for pumping water from the abandoned ironstone workings to prevent the pit from flooding.

Milton Ironworks and Elsecar Ironworks, leased to various tenants by Earl Fitzwilliam in the nineteenth century, had both been connected to the Dearne & Dove Canal basin at Elsecar by a stone sleeper block tramroad laid shortly before 1840. The growth of ironstone mining in Tankersley Park, and the expansion of Thorncliffe Ironworks at nearby Chapeltown, resulted in the tramroad being extended in the mid‑1840's from Milton to Thorncliffe via Tankersley Park. This extension, carried out largely at the instigation of Earl Fitzwilliam (who at that time owned the land upon which Thorncliffe Ironworks were situated), now facilitated the transport of ironstone to all three ironworks and also finished goods from Thorncliffe to the canal basin at Elsecar. The tramroad was worked by horses on the level stretches, with stationary engines for the incline sections, and parts of it are said to have remained in use until about 1880, the period when ironstone mining ceased. The type of rail used - either cast iron plates or wrought iron edge rail - is not known for certain, though as the tramroad arrived quite late on the scene one would expect it to have employed edge rails. Evidence derived from old maps of the area leads one to assume that it was laid to sub‑standard gauge. At some later stage in its history - certainly before about 1885 - the section of tramroad running from Lidgett to Milton and Elsecar was relaid with standard gauge permanent way to connect with the South Yorkshire Railway's single line branch at Elsecar, which was opened in February 1850 and later (1864) taken over completely by the Manchester, Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway. The Manning Wardle Engine Book shows that W.H. & George Dawes had two standard gauge locomotives delivered new to their Milton Ironworks in the early 1860's. These were KEADBY, works number 40, a class E 0‑4‑0 saddle tank with 9½in by 14in cylinders and 2ft 9in diameter wheels, despatched from Leeds on 30th December 1861; and MILTON No.5 (or No.5 MILTON), works number 99, a class B 0‑4‑0 saddle tank with 6in by 12in outside cylinders and 2ft 6in wheels, despatched exactly three years later on 30th December 1864. These locos would seem to have been used for shunting at Milton Ironworks, possibly also being used at Elsecar Ironworks and to bring ironstone from Tankersley Park for smelting at both works. The date of despatch of KEADBY to Milton suggests that the tramroad from Elsecar to Milton (and possibly to Tankersley Park also) had been relaid to standard gauge by 1861. The whole problem of dating the re‑laying of the tramroad is complicated further by the fact that the canal basin at Elsecar was re‑sited by filling in the last 100 yards or so of the branch canal. Charles Hadfield in Volume 2 of "The Canals of Yorkshire and North East England" (David & Charles, 1973) states that this was done in 1850 to allow for the building of the SYR. This is at variance with the 6in Ordnance map of the area published in 1854 (though actually surveyed in 1849‑50), which shows the SYR as built, together with the canal at its full (original) length. Perhaps the basin was filled in later to allow for a more comprehensive set of sidings to be installed by the SYR? The only positive (but contradictory) evidence I have so far been able to locate on this subject is a note from a local diary, compiled about the turn of the century, which quotes the original canal basin as being filled in about 1878.

Lidgett Colliery had initially been developed from the disused ironstone shafts by one John Fisher, who began driving from the shaft sides in 1879 to exploit the Lidgett Coal seam from which the pit took its name. After opening out the new pit bottom, Fisher, who had previously been manager of the ironstone mines, ran into financial difficulties and sold out to William Clarke, a local Doctor of Medicine, reputedly for £1,000. On 8th August 1883 the undertaking was registered as the Lidgett Colliery Co Ltd, with an authorised capital of £15,000 in £50 shares. Dr Clarke was Chairman of the new company, and the other six initial subscribers for shares were: Horace Walker of Wales village, near Sheffield; Thomas Vickers of Manchester; John Marshall of Sheffield; William Whitworth Matthewman, a colliery agent, of Doncaster; George Blake Walker, a mining engineer, of Tankersley; and Henry Stirling Walker, also of Tankersley. According to the Articles of Association, the new Company, provided it was incorporated before 1st October 1883, was to purchase the total assets of the colliery from Dr Clarke for £6,500. A somewhat grandiose start was envisaged, for the Company adopted its own coat of arms complete with motto - Vires Acquirit Eundo.[1] In retrospect, the whole venture seems to have been attended with a high risk for the Lidgett Coal was but a thin seam some 2ft 8in thick, of which only 2ft was top quality saleable material. It comes as no surprise, therefore, to learn that the initial coal winning by "pick and shovel" proved uneconomic but Dr Clarke quickly realised the benefits to be gained by the introduction of coal cutting machines. His gamble proved sound. Within just over two years output was raised from 700 to 2,000 tons per week. Even today, with the aid of modern technology, thin seam working has its quota of problems. In addition to these Lidgett had one more: its workings lay immediately to the north of a geological discontinuance - the Tankersley Fault - and were heavily watered! Some local people still refer to the pit as "Sludge Main" because of this it must be admitted that this nickname is more often applied to the "Footrill Hole" (drift) pit on Broadcarr Road, just south of Milton. The majority of elderly local residents know of Lidgett Colliery as "Pill Box Pit" because of Dr Clarke's close association with it! Virtually the whole of the royal because of this but it must be admitted that this nickname is more often applied to the "Footrill Hole" (drift) far as Black Lane to the south west where the Tankersley Fault acted as a natural boundary, and as far as Elsecar reservoir and Milton. To the north west it went almost as far as Hoyland Common and to the south east it was bounded by a line running roughly through Harley and Wentworth.

Lidgett's first known locomotive did not arrive until some years after the colliery commenced working. According to Society records it was Fox Walker 382 of 1878, a standard gauge class 131 0‑6‑0 saddle tank with 13in by 20in outside cylinders and 3ft 4in diameter wheels acquired second-hand from the Fair Oak Colliery Co Ltd at Rugeley in Staffordshire.[2] SUCCESS (the name the engine carried at Lidgett) was used to haul wagons on the top, almost level, section from Lidgett to Milton; from there they were lowered down an incline by stationary engine and finally assisted by horses from the foot of the incline into the yard at Elsecar. Since Lidgett pit is known to have been in production by 1879 or 1880, this raises the question of coal transport prior to the acquisition of the Fox Walker. Several possibilities spring to mind. The easiest disposal of the coal would have been its sale at local landsale yards, though as output increased this solution would not have been very satisfactory. Standard gauge wagons of coal could have been transported to the canal at Elsecar without the need of SUCCESS: horse traction could have been employed although the length of run on the top section would seem to preclude this. The most plausible explanation is that an unrecorded locomotive was used during the 1879-1885 period. What more convenient than for Lidgett to hire a Manning Wardle engine from nearby Milton Ironworks? Or for Milton to work Lidgett's traffic under contract? In the early 1880's the iron trade was in the throes of a trade slump and at such a time it is more than likely that surplus locomotive capacity existed at Milton. More substance is added to this theory when one takes into account the fact that Milton Ironworks was finally closed in 1884, mainly through lack of trade.[3] With a locomotive from Milton no longer available for working their traffic, the proprietors of Lidgett Colliery would be compelled to look elsewhere for other motive power about 1884. Is it not significant that SUCCESS was acquired at about this time?

SUCCESS (Fox Walker 382 of 1878) seen here on 14th June 1938 working for Earl Fitzwilliam's Collieries Co at New Stubbin Colliery near Rotherham. (G. Alliez, courtesy B.D. Stoyel)

Initially the only rail connection the colliery had was the private line to Elsecar that was rented from Earl Fitzwilliam. Maintenance of this line, which was laid with chaired bullhead rail on wooden sleepers, was the colliery's responsibility. Exactly how traffic was worked in this early period is now lost in antiquity but it is doubtful if the method differed greatly from that adopted in the latter years of the colliery's life, which is detailed later. In 1894 construction of the Midland Railway's extension of its Sheffield - Chapeltown branch to Barnsley commenced and the line was opened in 1897. Its course passed very close to the Lidgett Colliery and ran parallel to, slightly lower than, and immediately south of the private mineral line as far as Milton. Here the latter swung north and then turned due east to descend an incline into Elsecar, the Midland Railway passing under the head of the incline by means of an underbridge. Construction of the Midland branch did not pass without incident. There is little doubt that the mineral line to Lidgett from Elsecar was used by the contractors for this section of the Midland, Walter Scott & Company, to bring materials from the rail and canal head at Elsecar. It is recorded in a contemporary diary that on 4th September 1894 the "First MS&L wagon [was] taken up to Black Lane with Bridge for crossing". This refers to the bridge which subsequently carried the MR over Black Lane, about 400 yards south west of Lidgett Colliery. At this time access to Black Lane by rail could have only been achieved by utilising the Lidgett Colliery line. Even more intriguing, and more conclusive, is an earlier note made for 15th August 1894:- "A part of Steam Navvy fast under Lidgett screens"! Doubtless the colliery company had a few scathing remarks for Walter Scott & Co following this incident! The contractors had their own locomotives for assisting with the construction of the branch and there is no suggestion that SUCCESS was ever hired by them.

Lidgett Colliery entered into an agreement with the Midland Railway for provision of suitable siding facilities for traffic which they wished to despatch via MR metals. The agreement, dated 14th November 1895, was such that the MR was to construct at its own expense two sets of sidings, termed Empty Wagon and Full Wagon sidings, and situated respectively north west of Wentworth & Hoyland Common Station and north east of Skiers Spring Brick Works. Connections to these sidings and the private mineral line were to be carried out by Lidgett Colliery at their own expense. The latter was also to be responsible for marshalling intended traffic into a form suitable for collection by the MR.

Apparently the colliery had only one weigh bridge for taring railway wagons and this resulted in rather wasteful shunting operations. Empties were normally stored in the two sets of sidings to the south west of the main colliery screens, at the head of the branch. Unfortunately the weigh was on the other side of the screens. SUCCESS therefore had to shunt rakes of empties past the north side of the screens, and then take them back after weighing operations had been completed. Empties were then allowed to fall by gravity into any of three roads under the screens to be loaded with lump coal, cobbles or "slack" (fines) respectively. Fulls were collected by SUCCESS at the other side of the screens and weighed prior to despatch.

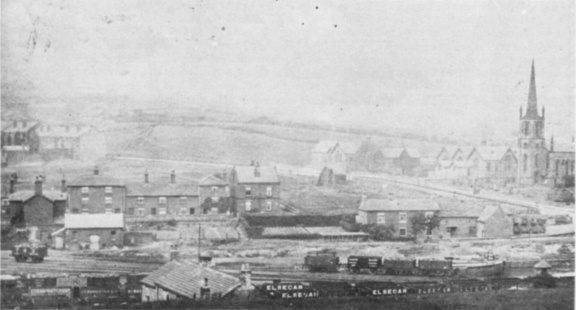

The canal basin at Elsecar, about 1900, looking north east. Earl Fitzwilliam's Simon Wood Colliery, known locally as the Planting Pit, is easily discernible in the background. In the lower middle of the photograph a barge is adjacent to the coal staithes (extreme right) used by Lidgett Colliery, and the line from the latter is in the right foreground. Note the barge on the left, loaded with pit props. (collection G. Palmer)

Traffic destined for the Midland was speedily dealt with, the necessary shunting involving few complicated movements. The wagons were simply collected by SUCCESS from the weighbridge and pushed back past the screens into the Empty Wagon sidings. Empties arriving were deposited in the Empty Wagon sidings by a Midland loco and collected by SUCCESS as required. It would seem logical for Lidgett to have adopted the system whereby empties from the MR came in at the Empty Wagon sidings and fulls left at the Full Wagon sidings but several old Lidgett employees are adamant that under normal circumstances all traffic to and from the Midland was dealt with mainly at the Empty Wagon sidings behind Wentworth & Hoyland Common Station. The Full Wagon sidings seem to have been used almost exclusively for traffic to and from Skiers Spring Brick Works. The shunting of traffic to and from the Empty Wagon sidings involved crossing the main Chapeltown to Birdwell road by means of an ungated level crossing and to safeguard against accidents a flagman on the crossing had control over a somersault signal used to regulate the progress of SUCCESS. According to a former employee this was "like those on the Midland Railway" and had an electric light behind the spectacle to aid visibility. It was undoubtedly the simplicity of this shunting which led to a decline in traffic down the incline from Milton to Elsecar - for the latter involved the maintenance of no less than four more ungated road crossings, not to mention a stationary engine and winding gear! The first of these crossings, on Broadcarr Road, was unmanned but all the others were protected by a flagman. If for any reason normal access to the Midland line via the Empty Wagon sidings was impaired traffic was brought in and taken out at the Full Wagon sidings which were, as related earlier, more usually employed by Skiers Spring Brick Works. As rail traffic for the brickworks was shunted by SUCCESS anyway they could hardly object to this arrangement.

Traffic for the MS&L branch and the canal basin at Elsecar had a somewhat more eventful journey. The rakes of fulls were pulled by SUCCESS from the screens to the sidings at Milton, by the head of the incline. On arrival the loco ran around the wagons and pushed them into a position where they could be attached to the incline rope. From here they were lowered down the single line incline in sets of two or three by an ancient stationary engine known locally (after its driver) as "Old Ned Green's Bobbin Engine"! This had a single horizontal cylinder with hand worked slide valves. At the bottom of the incline, which was just short of Fitzwilliam Street, they were detached from the steel rope and assisted into the yard at Elsecar by large horses. (Often gravity was found to be sufficient for working the fulls into the yard and the team of horses was more usually employed in pulling empties from the yard to the incline bottom.) The coal brought down in this way was then either despatched via the MS&L or loaded manually into barges from a staithe at the canal basin. Apparently the majority of the canal borne traffic found its way to Hull, presumably for shipment. A reverse procedure was adopted for empties at Elsecar destined for Lidgett. As related, these would be horse drawn (one wagon per horse) to the bottom of the incline and pulled up in sets - again of two or three wagons - to the top of the incline where they were placed in a storage siding to await collection by SUCCESS.

There seems little doubt that Milton incline was something of a thorn in the flesh of the Lidgett Colliery proprietors. By 1895, just before the Midland line was opened, coal production had reached 500 tons per day.[4] This was no mean achievement considering the difficult seam worked, even if 90 per cent of the coal was won by machinery. Since virtually all of this coal was taken away by rail to Elsecar in standard 8‑ton and 10‑ton wagons the incline had to deal with some 50 fulls and 50 empties per day. Little wonder that work started at 6am and didn't finish until about 4pm on a normal weekday. A double track incline with balanced working would have done much to solve the problem but doubtless the cost of such "modernisation" would have proved prohibitive. The gradient of the incline was not particularly severe, except at the very top, and at one time the company optimistically tried adhesion working on it with SUCCESS - the idea being to supersede the stationary engine and "streamline" operations. Indeed, SUCCESS had been purchased in preference to a four wheel loco for this specific reason. The attempt was rather short lived. On the last journey made in this fashion the loco was unable to haul two wagons up the incline: it eventually stalled and the driver applied the brakes, but to no avail. Gravity now took over, the driver and his mate jumped off, and the uncontrolled train crashed into some wagons in the sidings at Elsecar. It was fortunate indeed that the only damage resulting from this episode was the destruction of the wagons!

Another view of the canal basin at Elsecar, about 1903, but looking north west, with the village in the background. Four wagons on a spur in the lower right of the photograph are at the Lidgett coal staithes: the left hand wagon is being unloaded and next to it is a very clean example of a wagon in Lidgett Colliery livery. A barge stern can just be discerned to the right of these four wagons, whilst the lower foreground is occupied by wagons of Earl Fitzwilliam's Collieries Co. (courtesy E. Stenton)

With the opening of the Midland line Lidgett could have abandoned the costly incline working from Milton to Elsecar and sent all its traffic via the Midland. The only drawback to this would have been the loss of canal facilities at Elsecar, together with the alternative rail outlet via the MS&L at Elsecar. It would seem that Lidgett used the agreement they had reached with the Midland (cited earlier) as a "lever" to obtain more favourable terms with the MS&L. Lidgett's wish was that the MS&L, with the approval of Earl Fitzwilliam, should assume responsibility for operating the incline, but this did not meet with success.

Ultimately a compromise solution between Lidgett Colliery and the MS&L was reached by an agreement dated 9th July 1897, doubtless after spirited negotiations. The preamble to this agreement indicated that Lidgett had "for many years past been sending traffic from their colliery at Tankersley near Barnsley to be forwarded thence over the system of the [MS&L] Railway, ... also traffic to be sent over the Dearne and Dove Canal. [in] order to do so the Colliery Company have had to work such traffic over a private branch railway belonging to Earl Fitzwilliam by means of a Stationary engine and appliances connected therewith, and ... the Colliery Company applied to the [MS&L] Railway Company to take over the said private branch from their railway at Elsecar to the Stationary engines [sic] and sidings of the Colliery Company [at Milton] but [this] the [MS&L] Railway Company were unable to do and in lieu thereof it was arranged that the present Agreement should be entered into..." Lidgett Colliery was to continue to work traffic over the "said private branch" as before but the MS&LR was to pay the sum of £655 per annum towards the cost of maintenance of the line from Elsecar to the head of Milton incline. (Note that this was the only part of the private branch over which traffic from Lidgett Colliery destined for the Midland Railway could never conveniently pass. It would never do to subsidise traffic intended for a rival!) In return for this generous offer Lidgett Colliery had to pay 4d per ton on all traffic despatched over the private branch "and intended to be sent by the said [Dearne & Dove] Canal, such payment to include the toll for passing over a small portion of the [MS&L] Railway Company's property between the termination of the said private branch and the Canal basin..." The £655 towards maintenance was to continue as long as "the rent of the said private branch remains at One Hundred and twenty five pounds per annum and so long as the Company shall continue to send not less than 90,000 (ninety thousand) tons of traffic [per annum] from their Collieries to Elsecar to be forwarded over the system of the [MS&L] Railway Company..." Any subsequent increase or decrease in the rent of the private branch was to be shared equally by Lidgett Colliery and the MS&L.

A typical day's work for SUCCESS would begin with steam being raised in readiness for the crew arriving to start work at Gam. This duty was carried out by a night shift man from the colliery fitting shop-cum-power house where he normally attended to a set of Lancashire boilers. (These provided steam for a stationary engine which generated electricity used by the pit.) On Mondays to Fridays (inclusive) the loco worked from 6am to about 4pm; on Saturday the finish was often about 1pm. During this time SUCCESS would work traffic to and from the Midland Railway as required; also that to and from the incline top at Milton in connection with the traffic for Elsecar yard. In addition shunting was performed for Skiers Spring Brick Works, which despatched a considerable proportion of its output by rail. Two landsale "yards" were served - one in the pit yard immediately next to the loco shed, and a small one located near the incline top at Milton. Steam for the stationary engine which worked Milton incline came from two egg‑ended boilers and these were fired with coal kept in two or three wagons (on a short spur behind the engine house) which the loco exchanged for fulls when necessary. There was a brass foundry' at Milton (on part of the site of Milton Ironworks) which was served by a spur off the Milton incline: traffic for the foundry came up the incline in the usual way but SUCCESS was not used to shunt this siding.

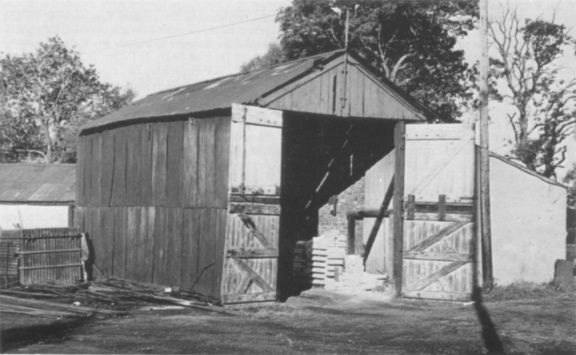

No shunting was carried out on Sundays, but the crew would turn up during the day to clean and service SUCCESS. This was done in the single road loco shed which was mainly of wood construction with a corrugated iron roof. It was capable of holding one loco only. They would also carry out minor repairs as necessary and occasionally attend to big end brasses and other parts subject to regular wear. The driver was rather proud of the appearance of "his" engine, which sported a rich brown-red livery and, in common with other products of Fox Walker, had several ornamental brass and copper fittings capable of taking a high polish. The name SUCCESS was painted on the tank sides in relief gilt capitals.

In the later years of the colliery's life it was always possible to see at a glance who was driving the locomotive. Progress with the regular driver in charge has been described as "smooth and stately": when he was absent the regular shunter deputised and conditions deteriorated to become "rough and jerky".

As the colliery had only one locomotive the problem of breakdowns must have been particularly acute, since no suitable motive power replacements (other than horses) could be easily obtained. George Blake Walker was the Agent for Lidgett Colliery and as he was also a Director of the Yorkshire Engine Co Ltd it is hardly surprising that major repairs to SUCCESS were contracted to the latter company. The earliest mention of Lidgett Colliery in Yorkshire Engine records concerns firebox repairs (a new back plate and tube plate), presumably for SUCCESS, though the relevant entry in the Drawing Office Order Book, dated 10th August 1888, is not specific on the point. A later entry in the same book, dated 28th August 1890, is of rather more interest, for under a Lidgett Colliery heading it states "Necessary repairs to Nunnery loco as arranged." Yorkshire Engine records show that during at least some part of 1890 Lidgett were hiring Nunnery Colliery No.2 (Fox Walker 216 of 1874) whilst their own loco was again under repair, this time having a patch fitted to the firebox. (Fox Walker 216 was an 0‑6‑0 well tank which formed part of an order dated 15th September 1873 for three class J locomotives with 14in by 20in cylinders and "underneath tanks" and was probably the engine illustrated on page 355 of RECORD 46.) As a further point of interest, Fox Walker 216, after its hiring to Lidgett, was rebuilt by Yorkshire Engine for Nunnery Colliery from a well tank to a saddle tank locomotive. The partial renewing of the firebox on Lidgett's own locomotive in 1888 and 1890 does not seem to have been effective, for a further Lidgett entry dated 5th June 1891 in a Yorkshire Engine Specification Book states:- "New boiler with smokebox tubeplate and firebox outer casing. New brass tubes... New copper firebox..." An additional entry for 21st December 1891 gives details of many items including "Extras as arranged with Dr Clarke. 1 pair of Buffer Planks...' An intriguing entry in Yorkshire Engine records for Lidgett Colliery appears in the Drawing Office Order Book for 19th December 1896:- "Retube Loco at Elsecar." This shows that repairs carried out by Yorkshire Engine for Lidgett Colliery were not all done at Meadowhall Works, Sheffield. Day to day repairs were carried out in the locomotive shed and at least one instance is known when new parts for SUCCESS were made by the neighbouring firm of Clarke & Steavenson, as detailed later. Facilities for heavy repairs at Lidgett were limited but Dr Clarke was able to make use of Earl Fitzwilliam's colliery workshops at Elsecar which were quite extensive. It is also likely that a loco was loaned by Earl Fitzwilliam's Collieries Company from time to time when SUCCESS was undergoing repairs, especially when one remembers that Skiers Spring Brick Works - latterly owned by Earl Fitzwilliam - was dependent on Lidgett for working its traffic. The next major entry for Lidgett in Yorkshire Engine records is in the Drawing Office Order Book for 1st August 1901 which gives details of repairs to a six wheel locomotive. Most of the items listed were minor but the firebox was to be tested to see whether it was capable of working 4½ years if a new set of tubes were to be put in. The engine was to be painted and varnished and returned within eight weeks. A later entry is virtual proof that retubing was not carried out in 1901, for sundry repairs detailed on 8th June 1903 included a new firebox and brass tubes: before being returned to Lidgett the engine was "to be painted only in places to make [it] presentable". During one of its visits to Yorkshire's for repairs, possibly that in 1903, the job of SUCCESS was performed by a small four-wheel loco (identity unknown) loaned by or hired from Yorkshire Engine.[5] The next mention of SUCCESS is in 1922 when the loco is specifically referred to by name in Yorkshire Engine Records when being repaired for its then owner, Earl Fitzwilliam's Collieries Company. (None of the previous entries in Yorkshire Engine records under Lidgett Colliery headings mention SUCCESS by name or works number, but this is frequently the case with owners having only one locomotive who probably never mentioned the name or number when writing to Yorkshire Engine.)

It seems that the colliery company owned no wagons of its own. Several were hired from an unknown company and as there were so many the hire company stationed an employee permanently "on site" at Lidgett for servicing them. In addition to axle greasing and the like he also carried out wagon repairs on a siding next to the two "empties" sidings at the extreme head of the colliery branch. Several Lidgett men recall that many of the wagons used latterly displayed "FLOCKTON WALLSEND LIDGETT COLLIERY" in white letters on a black background. ("Flockton Wallsend" was the trade name under which Lidgett marketed their particular type of coal.)

A rather humorous incident involving some wagons has been related to me. During the 1926 general strike, long after closure of the pit, an employee of the adjacent engineering works happened to notice someone digging in the yard near the former loco shed. When questioned, the man said he was digging for coal - rather to the amusement of his questioner. The digger had the last laugh though. At some time in the last years of the colliery's working a wagon smash had taken place somewhere near the loco shed due to rather careless shunting. In order to hush up the affair the wagon parts were rapidly taken away, and the coal was levelled out and then covered with soil and cinders. Needless to say, it didn't take the digger very long to locate this particular "seam" of coal!

A description of the actual working of the pit is of interest. In its very early days no form of safety lighting was used, and the colliery was referred to as a "candle pit" for this very reason. The winding engine was situated (on the dirt tip!) between No.3 and No.4 shafts and was in fact the original beam engine constructed at Elsecar in 1830 in connection with the ironstone mines which Lidgett Colliery superseded. It had a single vertical cylinder, 19in diameter by 48in stroke, and a flywheel of 16ft diameter. The winding drum was outside the engine house and was of the differential type. From the 5ft diameter side a single steel winding rope passed to No.3 shaft, and from the other side (6ft diameter) a similar rope passed to No.4 shaft. The engine was capable of raising two 5cwt tubs in each single deck cage. All three shafts were lined with deal "tubbing" and were 7ft 6in diameter: the two used for winding had pitch pine conductors for the cages. The Lidgett seam - the only one worked - was found some 250 feet below the surface at No.3 shaft. The colliery is of particular interest to mining historians because of the early widespread use of coal cutters. Briefly, these machines, which ran on rails, were used to undercut the seam in the 8 inches or so of low quality "bottoms" before the better quality (household) coal was blasted down with gunpowder. The "bottoms" (inferior coal) were not collected but thrown back into the "gob".[6] Usually an 80 yard face with four or five gates was worked in this way. The coal was hand loaded in tubs, these being mostly hand trammed until the main underground roadways were reached. Here endless rope haulage was used for the final journey to the pit bottom. The stationary steam engine providing power for this haulage system was located at the top of No.2 shaft and had two horizontal cylinders of 15in diameter by 30in stroke. An endless rope ran from the engine down the shaft to drive a series of pulleys from which further endless ropes were driven. Some haulage underground was done with the aid of ponies in districts where the roof was higher. What may have been the first coal cutter used here was one built in 1890 for Lidgett by the Yorkshire Engine Co Ltd, works number 466. It was actually the ninth coal cutter made by Yorkshire Engine and was later supplemented at Lidgett by a second similar machine (No. 842). These two do not appear to have been very successful as less than five years after their introduction no mention is made of them in a technical description of the colliery which appeared in "Colliery Guardian" for 1895. Gillott & Copley compressed air cutters were also employed at the pit but maintenance of air lines underground proved prohibitive and led to their partial replacement when electricity was introduced to the pit in 1893. All the compressed air cutters had been replaced sometime before 1903. The electric coal cutters were developed at the colliery by Mr C. Foster, the Enginewright, and proved so successful that Dr Clarke took out a patent in respect of the design and set up his son in a partnership - Clarke & Steavenson - which subsequently produced and marketed this type of cutter from premises adjacent to the colliery loco shed. It was eventually found unnecessary to run the cutters on rails and later models were fitted on sledges. Water was a particular source of irritation in the working districts of the colliery, especially in wet seasons. It made for very uncomfortable working conditions and required no less than five pumps (driven by compressed air) to keep it under control in various low parts of the seam. The main pumping engine, which removed water from No.2 shaft bottom into an artificial watercourse designed to drain the area, was originally a single acting condensing type with one vertical cylinder (4ft 2in diameter by 7ft 6in stroke) using steam supplied by two Cornish boilers. Like the winding engine, this was the original pump erected in 1830, its purpose then being to de‑water the ironstone workings. It was replaced (before 1903) by an electric three-ram horizontal pump located at the bottom of the shaft. Ventilation underground was effected by a Biram fan some 14 feet in diameter capable of exhausting 18,000 cubic feet of air per minute from No.2 shaft. Despite the fact that it was made about 1845 it was still giving good service fifty years later. Latterly No.4 shaft became the upcast (fan) shaft after No.3 had been enlarged and altered from circular cross section (7ft 6in diameter) to rectangular cross section (11ft x 9ft). This widening took some four months to complete, being done in such a way that normal coal winding operations were not interrupted. On completion of the work No.3 shaft was used for both coal and man winding.

By 1911 coal reserves were nearing exhaustion. Flooding of the workings was also becoming a major problem and the colliery eventually closed in November 1911, the workings being officially abandoned on 31st December 1911. Thos. W. Ward Ltd were responsible for demolition of the unwanted surface plant. They quickly dismantled the screens, which were mainly of steel construction, and took away the Lancashire boilers from No.3 pit for scrap. During the demolition, which occupied some twelve months, SUCCESS was not brought into use. Ward's set up a small stationary engine which drove a rope winch to haul pieces of scrap plate from the boilers across the Chapeltown - Birdwell road to the MR Empty Wagon sidings behind Hoyland and Wentworth Station. Here the pieces were loaded into railway wagons for despatch.

Some months after closure SUCCESS was steamed for its run to Elsecar, after being purchased by Earl Fitzwilliam's Collieries Company. It was collected at Lidgett by the Elsecar Colliery Engineer, "aided" by one of his fitters. Instead of SUCCESS being driven on the through road at the northern end of the screens at Lidgett it was taken on one of the roads under the screens, with somewhat disastrous results. The engine fouled the screens and its dome cover and safety valves were knocked off! The resultant escape of steam quickly emptied the footplate, but not before the fitter had been scalded. New safety valve parts were speedily made at Clarke & Steavenson's works and the whole episode was kept quiet.[7] (This event provides a fitting sequel to the episode involving Walter Scott & Co's steam navvy, described earlier. Lidgett Colliery screens seem to have been singularly unfortunate for, in addition to these two collisions, they were also subject to a small fire about 1904!) A few days after the accident the repairs to SUCCESS were completed and she was taken down the incline at Milton in steam, without braking assistance from the stationary engine. This time an ex‑Lidgett fitter was on the footplate! Being a six‑coupled loco, one of the first jobs which SUCCESS had at Elsecar was working the heavily graded dirt run from Simon Wood pit to a disused quarry north east of the colliery, and her rich brown-red livery was soon exchanged for one of green.

It would seem that the section of private railway between Lidgett and Broadcarr Road was dismantled shortly after the colliery closed. From about 1914 drift mines were established in Skiers Spring Wood by one Albert Adamson under a lease from Earl Fitzwilliam. Initially only "landsale" coal was produced, this being taken away by horse and cart to local coal yards. On 21st July 1921 Adamson entered into an agreement with the Midland Railway for moving his coal away by rail. The MR sidings previously laid down as Full Wagon Sidings (SK 371995) for Lidgett Colliery were modified so that they suited this purpose. Adamson had to pay £300 towards the cost of modification and provide his own tramway from one of his drifts to the railhead, together with a chute for loading the coal into standard gauge wagons. As a result of this agreement, Adamson had to ensure that all his traffic in and out was routed via the Midland Railway wherever possible in preference to any other company. He was also expected to pay in full for any future extension to the siding capacity. As far as is known, no industrial locomotive ever worked Adamson's Siding (as it was officially known). Empties were propelled past the screens on an "avoiding" line up to a head shunt by MR (later LMS) locomotives: these wagons were then allowed to fall through the screens by gravity. The screens established by Adamson appear on the 1931 25in Ordnance Survey map of the area but are merely identified as "Skiers Spring (Coal Pit)": they should not be confused with the present day NCB Skiers Spring Colliery, which is located about 400 yards to the west. Adamson's drift mines actually connected underground with the "Footrill Hole" drift mine located at SK 331995, which he also leased. The only seam worked was the celebrated Barnsley Bed, some 9ft thick, though the full thickness was not exploited. When Adamson's lease for these pits ran out Earl Fitzwilliam did not allow it to be renewed, preferring to work the drifts himself using men from his own nearby Elsecar Main Colliery. A typed entry in the MR siding agreement, dated 8th May 1925, states "Now Earl Fitzwilliam": additionally the head shunt was "extended about 200 feet". On 15th January 1926 Earl Fitzwilliam entered into a new agreement with the LMS concerning Adamson's Siding whereby the LMS were to maintain the sidings at their own expense, and in return could employ them for their own use, provided that this did not interfere with traffic at the screens. For his part, Earl Fitzwilliam was to build, on LMS land, a wagon weigh for which he had to bear full maintenance costs. As with Adamson's agreement, a restrictive clause was added to ensure that traffic generated by the siding went by LMS metals in preference to those of other companies. The siding was normally only expected to produce loaded wagons for southbound traffic but the LMS would accept northbound traffic provided it was in blocks of not less than 150 tons. As a result of the 200ft extension to the headshunt, this now crossed a farm track on the level and Earl Fitzwilliam was obliged (per the agreement) to provide a lookout man by the level crossing when shunting was taking place. The closure of the "Footrill Hole" and the associated drift pits about 1931 resulted in the only underground fatality at the pit. The undermanager, Reuben Simpson, was killed when the abandoned levels were drawn.[8] As related earlier, the "Footrill Hole" was known locally as "Sludge Main" because of its acute water problem - caused presumably by the proximity of the workings to the surface. Incidents involving Blackdamp were also common. Whilst not an inflammable gas, its presence caused oxygen starvation and made breathing underground rather difficult at times. Ventilation was achieved by a fan (cupola) shaft at SK 373998: this had a fire at the bottom which heated the stale air and caused it to rise out of the underground workings. On 3rd April 1935 Earl Fitzwilliam's Collieries Co wrote to the LMS giving them permission to recover the rails at Adamson's Siding at their own convenience as the siding accommodation was no longer required.

The remainder of the former Lidgett line, from Broadcarr Road to Elsecar, lay dormant until about 1930, when it was mostly dismantled. Sections crossing public highways were left in place to retain the railway wayleave but all have now been covered over with tarmac.

Maps of the canal basin at Elsecar dated about 1890 show the line leading to Milton as eventually going to High Elsecar Colliery as well as Lidgett. The former colliery, located near the Furnace Inn, Milton, was also known as Upper Elsecar Pit. It was actually an extension of Elsecar Old Pit - of which the "Footrill Hole" on Broadcarr Road was a part - and ceased coal winding on 24th October 1888. Its history is rather obscure, and it is said to have closed virtually overnight because of a dispute involving a proposed increase of ¼d per ton of coal taken from the pit to the head of Milton incline.

The brickworks at Skiers Spring continued to work until closure in 1919, and from October 1911 was supplemented by a pottery works established on the site by Earl Fitzwilliam. Brickmaking had been first attempted here before the local ironstone mines closed, and the works started up in the summer of 1877. One of the original partners responsible for developing the works was a James Smith, and although later taken over by Earl Fitzwilliam the works was always known as Smith's Brick Works. Bricks were made from a composition derived from two convenient local sources - a claypit just to the south of the brickworks (on the other side of the Midland line) and neighbouring shale tips, legacies from the old No.1 and No.2 ironstone mines. The claypit served a double purpose, because a 30in seam of coal (Kent's Thick Coal) outcropped at this point and proved a useful fuel for firing the brick kilns. Both clay and coal were transported from the claypit to the brickworks by means of a short narrow gauge tramway which ran under the Midland line when this was built. The tub run was in use by about 1891 but seems to have had a short life as it does not appear on the 25in Ordnance map for 1905. From what I have learned from local residents it appears to have been temporarily dismantled during the period when survey revisions for the 1905 map were carried out and thereby avoided inclusion. At one stage the tramway was hand worked but later an endless cable was installed, the tubs (capacity 5‑6 cwt) being clipped singly to this for haulage to and from the claypit. An unsuccessful attempt was made to re‑open the works some time following closure. but the first two new firings produced unsaleable cracked bricks. This was probably because the new owners tried to use a new supply of blue bind from other shale tips without first removing the small flecks of fossilised shells known as "lime balls". During baking these shells decomposed and gave off gases which caused swellings and cracks within the body of the bricks. A knowledgeable former employee had been asked to return and help overcome this problem but he had lost an arm in a mixer at the works some years previously and was not over-anxious to go back! Further information on this subject is not available and I can only presume that after Lidgett closed, the few wagons needed for brickworks traffic were shunted by Midland and LMS locomotives.

Industrial archaeologists can still find much of interest in the area. The basic remains of Lidgett Colliery loco shed (SK 363988) today stand in the yard of Arthur Hague Ltd, manufacturers of nuts and bolts. This company took over the premises of Lidgett Engineering Co Ltd - successors to Clarke & Steavenson - who had utilised the loco shed as a blacksmith's shop. The colliery power house (SK 364989) is now used by Lidgett Garage Ltd. Visitors to the National Coal Board's loco shed at Skiers Spring approaching via Stead Lane will no doubt have seen the brick bridge abutments (SK 369994) just to the north of the ex‑Midland line. This is the point where the Lidgett line to Milton crossed. From here to Broadcarr Road the route of the line can be followed as a rough path on overgrown earthworks, and the head of the sidings associated with Adamson's drift mines is still marked by a sudden change in ground level on the path (SK 372997). Remains of the screens served by these sidings are still visible at SK 371995. The stone faced entrance of the "Footrill Hole", now gated, is visible from the road in the garden of the "Footrill" cottages. At Broadcarr Road (SK 373997) a section of track where the line crossed on the level was still visible as late as 1973, when it was finally covered with tarmac. The incline top at Milton (SE 375001) has been tipped on and levelled so few original earthworks are visible save those leading towards Broadcarr Road. From here on the course of the line is a rough, broad pathway from Milton which crosses over the ex‑Midland line by means of the original bridge and runs down to Elsecar. Walking up the incline nowadays gives a fair indication of the gradient profile as it was, assuming little subsidence has taken place. The bottom section, between the canal basin at Elsecar and the Esso garage on Fitzwilliam Street, was virtually level and is still referred to as "up the lineside". It has recently been tipped on and the whole surrounding area levelled. From the garage the incline towards Milton now begins to rise appreciably; first at about 1 in 20 and eventually at about 1 in 15. This gradual increase in gradient produces a concave profile which is clearly visible from the bottom. Traces of the original horse worked tramroad are also visible on the incline, for about half way up a few stone blocks can be located at SE 380000. At Elsecar, by the long disused and partially filled-in canal basin, the start of the lines to Milton are still in situ connected to the BR sidings here but two of them (disused) just disappear under the tarmac of Wath Road. The third is now a buffer stopped spur which sees little use. No trace remains of the loop which passed to the south west of Elsecar gasworks and led directly into Elsecar Ironworks. This loop, laid on the path of the tramroad which ran to the original canal basin, was lifted in 1914 when extensions were made to the gasworks.

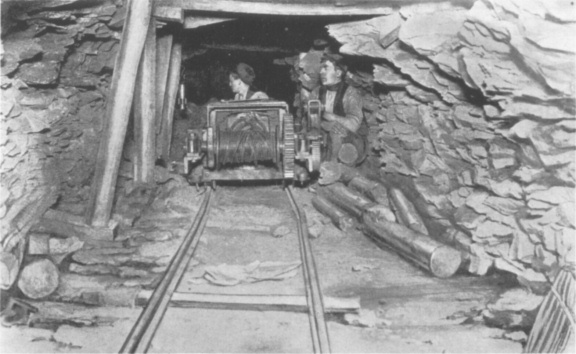

A Clarke & Steavenson's rail-borne coal cutter being moved in the cross gate between two ends of a longwall face at Lidgett Colliery. For this operation the cutting wheel had to be removed and was carried back separately to the start of the face being undercut. The track gauge is 1ft 9in. (collection T.J. Lodge)

No traces remain of the brickworks at Skiers Spring or its associated clay pit. The former has long been demolished and its site later occupied by Skiers Spring Colliery[9], though not immediately. The clay pit, in fact, was filled in when this colliery was being sunk, and during the Second World War its site was used by the Ministry of Fuel & Power for opencast coal despatch sidings. Actually there were two sets of such sidings at Skiers Spring: one on the clay pit site, immediately adjacent to Broadcarr Road, at SK 369991, and a further set directly opposite on the down side of the ex‑Midland line, at SK 368992. They were known officially by the Ministry as Wentworth South Sidings and Wentworth North Sidings respectively. The full history of opencast operations in this area is complicated by the fact that an earlier set of sidings - the old MR Lidgett Empty Wagon sidings behind Wentworth & Hoyland Common Station -were modified in the early 1940's for use in connection with opencast coal screening. By the mid‑1940's opencast coal destined for despatch from these sidings was graded at Wentworth Screens, situated at SK 377976 on Hague Lane about a mile west-south-west of Wentworth village. Opened in 1944, these screens were supplied with coal from an opencast site also on Hague Lane. At this site the contractors, Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd, used several locomotives on an isolated standard gauge system for some eight or nine months assisting with the removal of top soil to expose the coal. The SLP locos used are thought to include the following, which were all inside cylinder 0‑6‑0 saddle tanks: 195 ALMA, Hunslet 1855 of 1937; 271 ARK ROYAL, Manning Wardle 1519 of 1901; GIRL PAT, Hudswell Clarke 1679 of 1937; SLP No.1 RISLEY, Hudswell Clarke 1606 of 1929; 206 ALLENBY, Manning Wardle 1379 of 1898; and 329 THE HUNTER, Manning Wardle 723 of 1878. After use at Wentworth the locomotives were dispersed to a number of other SLP contracts up and down the country and at least one of them, GIRL PAT, is understood to have been converted to oil burning and sent to a contract in Egypt. Coal from the opencast site on Hague Lane was taken by road lorries to Wentworth Screens, and after screening the coal was transported, again by road, to the sidings behind Wentworth & Hoyland Common Station by now officially referred to as Harley Stocking Ground. Here the coal was dock loaded into railway wagons until the closure of these sidings in 1947. An agreement between the Ministry of Works (acting on behalf of the Ministry of Fuel & Power's Directorate of Opencast Coal Production) and the London, Midland & Scottish Railway shows that the MOF&P were allowed to shunt wagons with their own locomotive over LMS metals at Harley Stocking Ground and also obtain water - presumably for the locomotive - from the Station supply. The Ministry also had full use of the Railway Company's weigh office at the Station. According to a one‑time employee of SLP, Harley Stocking Ground was shunted for several months by MONTEVIDEO, an inside cylinder 0‑6‑0 saddle tank by Hudswell Clarke (1683 of 1937). This locomotive, not the property of the MOF&P, was actually owned by contractors Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd, their No.55, and may 'have also been employed for some time on the isolated system on Hague Lane. Harley Stocking Ground was closed probably because of its rather cramped nature for the tonnage of coal involved and replaced by the two sets of sidings at Skiers Spring. Both sets - later operated by the Opencast Executive of the National Coal Board - each had its own locomotive shed and worked independently. During the early 1950's, when the surface installations at Skiers Spring Colliery were expanded, the NCB took over the Opencast Executive's Wentworth North Sidings and locomotive shed for their own use. As such, these sidings are still in use today, together with the former Opencast loco shed, which now houses TL13, a four-wheeled Vanguard diesel-hydraulic locomotive (Thos Hill 142C of 1964). The despatch of opencast coal from Wentworth South Sidings finished about 1953 but the sidings themselves remained in use until about 1956 as empty wagon storage for Skiers Spring Colliery: today this site is used by Cawoods Transport Ltd, road haulage contractors. An interesting point is that plans were drawn up by the Opencast Executive to transport coal by rail from Wentworth Screens to Wentworth South Sidings but in the event the proposed rail link - about a mile in length - was never put in. Society records show the locos used by the MOF&P and Opencast Executive at Skiers Spring in one collective list. In view of the above can anyone provide information with regard to their actual individual allocations at Wentworth North or South Sidings? Further information on locomotives used by Sir Lindsay Parkinson & Co Ltd at Harley Stocking Ground and the opencast site on Hague Lane is also welcomed.

Lidgett Colliery loco shed on 19th October 1972. Few original parts remain in this structure save the wooden doors and gable ends, also parts of the wooden frame visible inside. (T.J. Lodge)

In conclusion I wish to thank all those who have provided information for this article, particularly Messrs N.L. Cadge, A.K. Clayton, L. Foster, G.W. Green, A. Parish, K.P. Plant, E. Stenton and A.J. Warrington; also British Railways Divisional Office at Sheffield, and the NCB Opencast Executive. I am greatly indebted to Mrs Stenton for her hospitality and willingness to allow me access to diaries and notes made by her grandfather Mr G. Johnson, one time deputy at Lidgett Colliery.

1 Roughly translates as "Strength through Progress":

2 Fair Oak Colliery was closed in 1884, the Company going into liquidation sometime before October of that year. The Fox Walker was part of the disposable plant, which was reported on 22nd May 1885 as all sold.

3 The final closure of Milton Ironworks took place because George Dawes refused to take a further lease on the property from Earl Fitzwilliam due to the economic conditions then prevailing. Eventually the plant was dismantled and put up for auction: three locomotives were advertised as being for sale on 6th July 1885.

4 Output was maintained at this figure until the colliery was closed in 1911.

5 This hiring is not recorded in surviving YE records. Two second-hand 12in 0‑4‑0 saddle tank locomotives then owned by YE are possibles - 259 of 1875, class Bx, purchased in July 1900 from Ashbury Railway & Iron Co Ltd in part payment for new locomotive 612 of 1900: and 288 of 1876, class Dx, acquired by November 1902 from Chas Cammell & Co Ltd, possibly in part payment for new locomotive 629 of 1902.

6 The "gob", or goaf, is the space created by the removal of coal from the strata. It can provide an area where methane gas (firedamp) collects and so is often filled, either with waste rock or by encouraging the roof to collapse deliberately.

7 This mishap was remarkably similar to the accident at Caddir (see RECORD 50, page 117) and presumably should have been reported to the Board of Trade under the provisions of the Boiler Explosion Acts, 1882 and 1890.

8 This consisted of withdrawing the timber supports so that the main underground roadways were encouraged to collapse.

9 Detailed consideration of Skiers Spring Colliery and the opencast sidings at Wentworth North and South are considered to be outside the scope of this article.

'ON SALE - TWO LOCOMOTIVE ENGINES FOR RAILWAYS 4 feet 8½ inches gauge; large copper firebox, & 120 brass tubes, 2 inch diameter; driving wheels, 5 feet 6 inches diameter, and two pairs carrier wheels, 4 feet diameter, 13 inch cylinders, and 18 inch stroke. Made by one of the first makers in Lancashire perfectly new, and could be delivered immediately. For further particulars apply Mr Joseph Johnson, iron merchant &c, Canning-chambers, Liverpool.'

("Mining Journal," 10th July 1841. – MJM)