| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© JUNE 1969 |

LITTLE EATON TRAMROAD

SYDNEY A. LELEUX

The letter on page 165 of RECORD 16 referring to Denby Hall Colliery in Derbyshire mentioned the little Eaton Tramroad. This 3' 6" gauge horse-operated line was authorised by the Derby Canal Act of 1793 and its construction was largely the work of Benjamin Outram; it was opened in 1795 and closed in 1908. The tramroad ran from the terminus of the Derby Canal at Little Eaton northwards to Smithy Houses, a distance of four miles, and then continued for a further mile to Denby Hall Colliery. In this area were several branches; to Salterwood North Colliery near Marehay Hall, Denby Pottery and Henmoor Colliery. The Act authorised branches to Smalley Mill and, for the sole use of the Earl of Chesterfield, one to Horsely Colliery*, but these were never built. Betram Baxter's "Stone Blocks and Iron Rails" (David and Charles, 1966) from which some of the above information was obtained, has a number of references to the construction and operation of the tramroad. A bridge remains at Little Eaton and a culvert at Smithy Houses, in addition to general earthworks.

A set of eleven National Coal Board photographs yield much information about the tramroad. The main line was single with passing places at intervals. Between the rails the ground was always made up level with the tops of the sleeper blocks to provide a clear surface for the horses. Outside the rails it would appear that the ground was more often level with the tops of the blocks than not. The rails which were about a yard long and of L−section were thicker and taller in the centre than at the ends. They were spiked to the sleepers, either through a notch at the end of the rail so that one spike secured two rails, or through a hole about an inch from the end so that one spike was needed for each end of each rail.

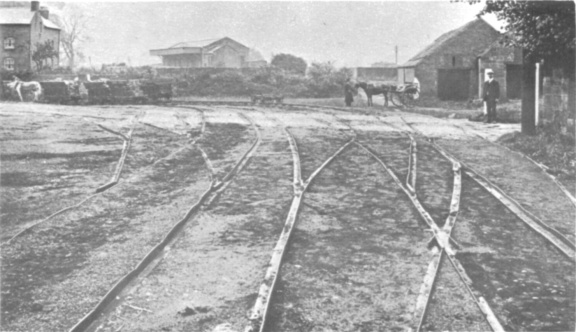

Points needed two special types of rail plate. The switches were V−shaped with a flange along one leg only. Pivoted between the outer ends of the arms was a metal finger which lay either against the flange, or across the tread of the rail. The two switch plates for a single point were mirror images of each other. At the crossing was an X−plate which had flanges along the inside of the arms at one side of the crossing, and on the outside of the arms at the other. These outside flanges continued along the crossing arm for a few inches to form a guide into the crossing. At the intersection was a finger, pivoted at the apex of the arms with inside flanges. No lever or other mechanism was provided for moving the fingers, so they must have been moved by hand or boot.

Where the track crossed roads a checkrail was used to maintain a clear path for the wheels. This might have been achieved by special rails of U−section, but the photograph is not sufficiently clear to be certain.

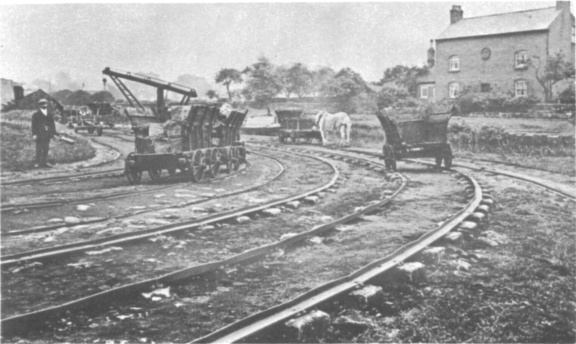

The wagons were wooden and rough measurements from the photographs would suggest that the bodies were 3' wide, 5' long and 2' high; they were carried on four narrow-spoked flangeless wheels 2' 3" in diameter. All of the body frame was external, one end of the body being permanently open with the load held in by two horizontal chains across the opening. To increase the capacity (Baxter gives the load as 33 to 37˝ cwts) the sides were topped by foot wide boards which sloped outwards slightly. These boards had wooden framing which extended beyond the edges into brackets on the wooden side. Braking was by placing sprags through the spoke wheels.

* "The Derbyshire Miners" by J. E. Williams, page 21

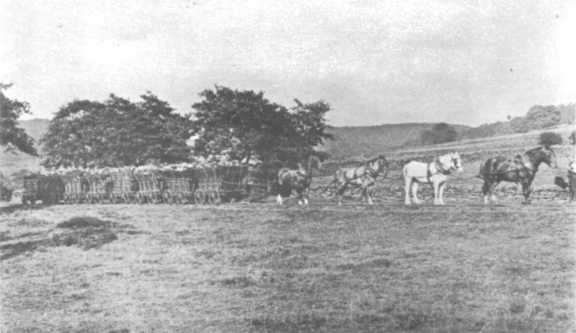

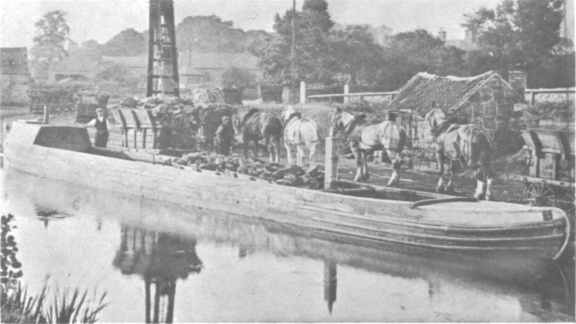

Eight wagon train en route to Little Eaton.

Little Eaton Wharf, pointwork. Crossing plate in right foreground and switch plates on all lines just beyond Midland Railway goods shed in the distance.

Little Eaton Wharf. Note the crane, open ended wagons, shunting horse and rails on stone sleepers.

Little Eaton Wharf. Note the coal containers in the boat, empty underframe in front of the first horse, and harness details including rear horse attached to wagon underframe. Midland Railway signal box behind the crane.

A crane, used to load the coal into boats, supported a four-piece chain sling, the arms of which were hooked into the eyes at the top corners of the wagon body. This was then lifted from its underframe and lowered into the boat which could hold four of the wagon bodies. The arms of the sling appear to have a quick release gear at their midpoints so perhaps some wagons were emptied into the boats.

All the photographs appear to show the same train, but there is nothing to suggest that it is anything other than a typical example. The eight wagons were hauled by four horses in single file, led by a man at the head of the leading horse.. The harness was designed so that any number of horses could be used, and in any order. From the collar a pair of broad leather straps ran along the horse's back and joined under its tail. Just above the tail were two transverse straps which hung down on either side of the horse. There was another broad transverse strap fastened to the longitudinal straps a short distance behind the collar. On both sides of the horse a length of chain was fastened to the collar at about '4 o'clock' and '8 o'clock'. It then passed through a ring attached to the broad transverse strap. A light strap, joined either to the broad strap or to the chain, passed loosely under the horse to the corresponding position on the other side. One of the lighter rear transverse straps was secured to the chain at a point level with the front of the horse's leg. The other rear strap was fastened close to the ends of a light piece of round wood to the ends of which the chain was secured. The wood acted as a spacer to prevent the chain biting into the horse's flesh. Horses were coupled together by lengths of chain from either end of the spacer to either side of the following animal's collar. The rear horse was harnessed to the train by chains from the end of the spacer to rings on the wagon. These rings were about half way up the corners of the closed end of the wagon body, for use with loaded trains, and on the outside of the dumb buffers for the empties. (If the horse had been harnessed to an empty container they would no doubt have pulled it off its underframe!) The leading horse had an extra narrow strap from about its tail loosely along the let side to its bit to act as a rein. It would appear that one horse was kept at Little Eaton for shunting.

I am grateful to the National Coal Board for permission to reproduce these historic photographs.

For the record….

"The Horseless Carriage on an Early Scotch Railway. - An attempt in this direction was actually made shortly after the inauguration of the Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway - Scotland's earliest line, and now part and parcel of the North British - before the claims of the locomotive had been recognised. A few gentlemen interested in the trade of the district tried the experiment of propelling wagons by the aid of wind, using umbrellas as a substitute for sails, and were gratified to find the truck on which they were seated moving along for some distance with the favouring breeze. The return journey, however, in face of a contrary wind and the improbability of tacking, had to be made by the experimenters putting their shoulders to the wheel" ("The Railway Engineer," August 1896 - KPP)