| THE INDUSTRIAL RAILWAY RECORD |

© APRIL 1968 |

RAILS TO THE WELL

FRANK JUX

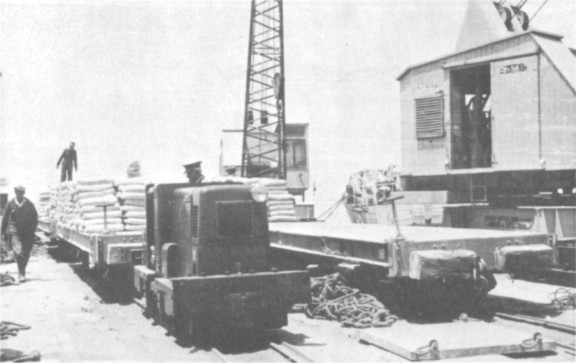

If you take the Thesen's ship to Port Nolloth on the Namaqualand coast you will find that rails lead off the tiny concrete jetty, and that all the off-loaded cargo is hauled away in 2ft bin gauge wagons by Ruston diesels. Port Nolloth is but a lonely village in a barren and wave-beaten coast. The nearest towns are over fifty miles distant and they are scarcely bigger or greener. Sand dunes stretch miles inland, rising into a stony waterless succession of hills and mountains. It hardly ever rains and when it does it is little more than a sea mist that the dunes absorb like blotting paper. Water is one of the essentials, and is found only by sinking wells; the nearest lies some five miles inland and is the present terminus of the railway. Ever since the harbour was built water has been hauled in over the same railway that runs on to the end of the jetty.

But of course that is not the whole story. Port Nolloth is a perpetual question mark. It serves all of Namaqualand, but the traffic from the dry interior would not support it were it not for the thousands of tons of stores and equipment that are unloaded for forwarding to the diamond mines of South West Africa and the Namaqualand coast. It is the only private port in South Africa and is owned by the Consolidated Diamond Mines of South West Africa Ltd. They operate what are probably the richest diamond workings on Earth along the South West African coast and this is a story in itself. CDM are but newcomers to the scene, for they took over the port about 1961, rebuilt the jetty, and operate it with a fleet of five Ruston diesels and numerous wagons taken over from the previous owners. They rebuilt the loco shed also, and it is no longer any match for the twenty-one steam locos that were once on the roster. The rails are being relaid in places and a rocky ride may mean that the old track has been eaten through beneath the sand. 'Those that are taken up show bolt holes on the bottom edges - they were not spiked but bolted to the sleepers with fang-bolts. For all anyone knows they may well date back to 1869 when the rails were first laid.

It all started in 1850 when Phillips & King of Cape Town bought mineral rights near Springbok. In no time at all plenty of small mines had been started, but only two companies survived for any length of time - Phillips & King, and the Concordia Copper Mining Company. Copper ore from the mines was precariously loaded into ships lying offshore along the wind swept coast and despatched overseas for smelting. Transport to the coast with mules and ox−wagons was a tedious business, with a drop of three thousand feet from the mines to the sea, through mountain passes and heavy sand dunes. By 1860 Phillips & King realised that if output continued to increase more equipment and resources would be needed. A prospectus was therefore issued to form the Cape of Good Hope Copper Co Ltd to take over and develop the partnership's mines and to build a railway inland from a jetty to be constructed at Port Nolloth. The immediate objective was to cross the sand dunes as more trouble was encountered crossing their twenty miles or so with heavy load, than in negotiating the eighty miles of mountains.

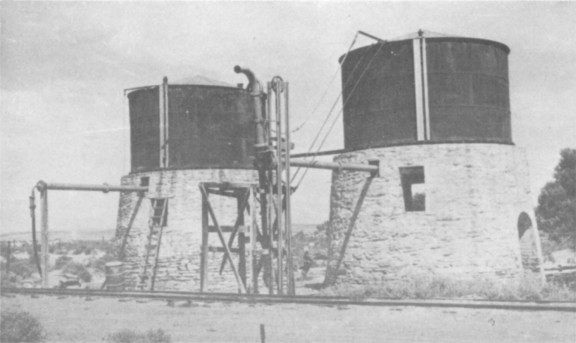

"Two Tanks", the present terminus of the line at Five Mile Point. (Author)

One of the Ruston diesels shunting the jetty. (Author)

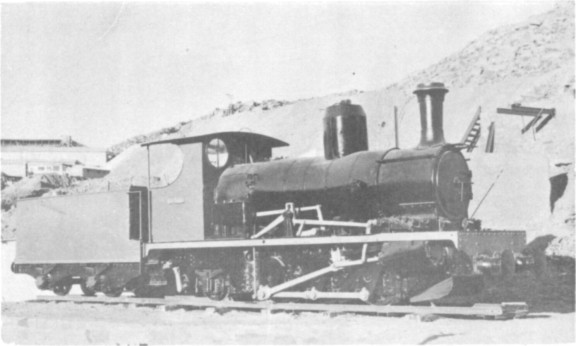

CLARA, the preserved locomotive at Nababeeb, was built by Kitson as an 0−6−2 tank, works number 3486-T258 of 1891 and supplied new to the line. (Author)

Tracklaying was commenced in 1869 from the Port and reached the main minim area at O'Okiep by 1876. The rails were light with longitudinal sleepers and were designed for mule traction. It was not until 1886 that the track was improved and steam locomotives took over the haul on the first twenty-two miles. In the next few years the track was relaid and loco haulage was used throughout. All in all the railway was a feat of engineering. Water had to be found for the locos (most of the stations seem to have been water stops with circular water tanks and fierce grades had to be climbed. Forty-seven and a half miles from the coast the worst part of the climb was reached, and the next seven and a half miles rose 1330 feet, with grades of up to 1 in 19 and the line hanging on the side of the mountains. Present day travellers drive on a road over part of the trackbed, and the remains of three crumpled wagons strewn down the hillside graphically illustrate the hazards involved in operation of the railway. The line throughout to O'Okiep and Nababeep was about a hundred miles long and abounded in curves and gradients. However the weekly passenger train was free, and twenty loaded wagons of coal and merchandise from the Port or ore from the mines raised the echoes of the mountains behind two Kitson 0−6−2 tender locos. It would have been nice to have seen the yard at Port Nolloth a bustle with activity with rows of locos on shed or being overhauled in the workshops, and a bevy of ships in the harbour loading copper for Swansea.

After the Cape Copper Company had opened their line, the Concordia Company (or their successors, the Namaqua Copper Company) decided to rail its ore to Port Nolloth also, and built their own line from their mines near Concordia to join the main railway just north of O'Okiep. From the junction the Cape Copper locos took over. In 1905 the Namaqua Copper Company had four locos in operation.

* * *

Copper mining ceased in the area in 1928. The richer ore had been worked out and no method was available to make the low grade ore pay. For almost ten years the railway lay dormant. Then in 1937 the O'Okiep Copper Company was formed to reopen the mines and install new separation plant that would render the lower grades of ore economical to mine. They bought two new diesel locos to shunt around the mines and operated the railway until 1942. They then decided to abandon the railway and send the output of copper from the smelter by dirt road to the railhead at Bitterfontein, over a hundred miles to the south, whence it was sent to Cape Town for shipment.

Port Nolloth itself has never been adequate as a port since steamers increased in size from the days of sail. Only coasters can enter the harbour, and then only at full tide. Consequently the cargo is unloaded without break to enable the following tide to be caught for the return journey to Cape Town. Three boats a week handle some 5,000 tons of cargo a month at the present time.

And so the clock has turned full circle and the railway has receded from O'Okiep. The rails were sold in 1943, but strangely enough a loco or two lingered on in O'Okiep village, no doubt almost forgotten. In 1966 a local magazine ran a feature on the area and the site was tidied up. One loco was retained, painted up and placed on a pedestal by the gate at the Nababeep mine.

CLARA is the last of the mountain locomotives.